Islamic Urban Centers (661–1300 CE)

Back to al-Ḏahabī’s Taʾrīḫ al-islām. The present dynamic cartogram shows how the prominence of major urban centers was changing over time. The focus is again on “descriptive names” (nisbaŧ) and the “size” of each urban center on the cartogram reflects the number of individuals with “descriptive names” that refer to that urban center. A “prominent center” in the current dataset is a place with which at least 10 individuals from Ta’rīḫ al-islām are associated1 (the overall number of individuals in the current dataset is slightly over 29,000 for the period of 661–1300 CE). Each frame features the names of the top 15 urban centers (the largest among them gradually change their hue from green to red).

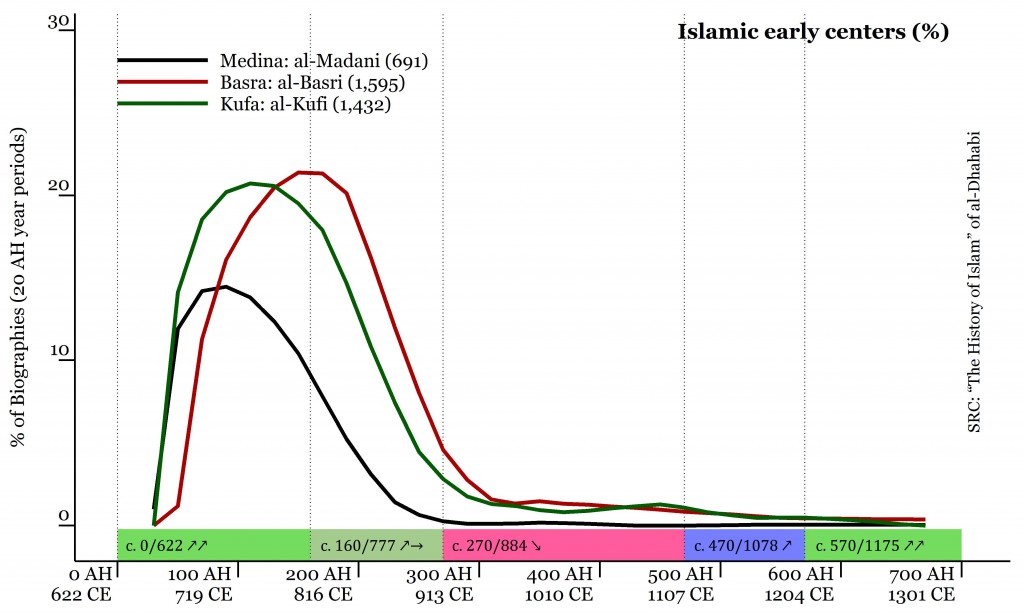

The cradle of Islam, central Arabia is the most prominent region in the early period. Major urban centers of this region are Mecca/Makkaŧ (269) and Medina/al-Madīnaŧ (691), but their cultural prominence soon shifts to the main garrison cities of lower Iraq: Kufa/al-Kūfaŧ and Basra/al-Baṣraŧ. The decline of central Arabia starts around 100/719 CE and by 250/865 CE this region is diminished to a marginal province. (The south Arabian cluster displays a similar trend.)

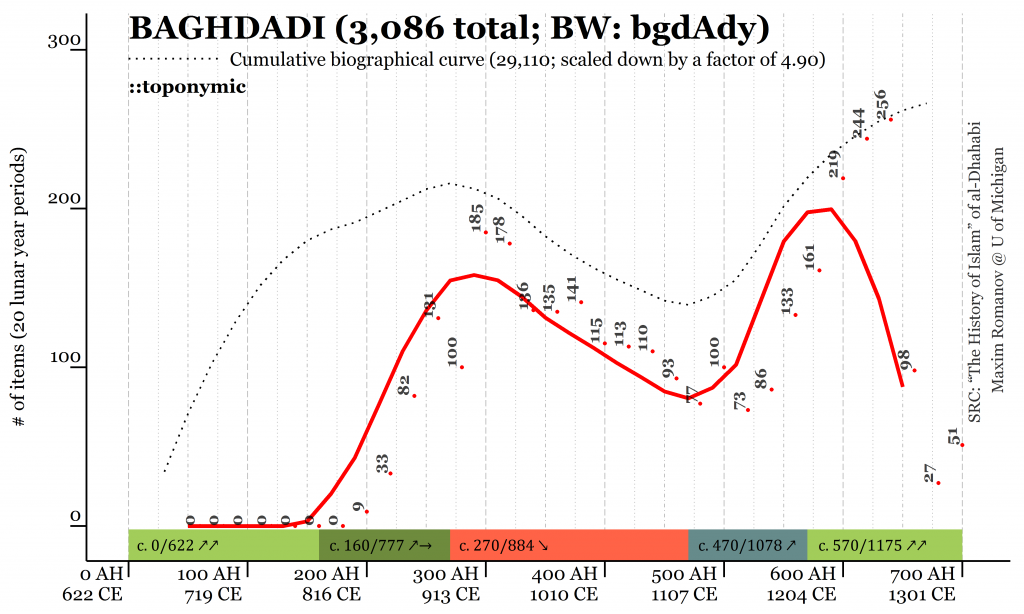

Iraq very quickly becomes the central region and maintains this status for the most of the period covered in Taʾrīḫ al-islām. During the early period its prominent urban centers are Basra/al-Baṣraŧ (1,595) and Kufa/al-Kūfaŧ (1,432), but the prominence of these garrison towns is soon dwarfed by Baghdad, the new capital city, and they practically disappear from the social map of the Islamic world by around 300/913 CE. Baghdad remains the dominant urban center not only for Iraq, but for the entire Islamic world until the beginning of the 13th century CE. Other major urban centers of this region are Wāsiṭ (401) and al-Anbār (83).

The rapid growth of Iraq comes to a halt around 200/816 CE—at this period the Caliphate is being torn apart by the civil war between al-Amīn and al-Maʾmūn, the sons of great Hārūn al-Rašīd (r. 786-809 CE), who decided to divide the Empire between them. The province falls into clearly visible decline. In the course of the 9th century the power slips from the ʿAbbāsid caliphs: first into the hands of the military commanders of their slave armies, then—the Būyids (932-1055 CE) and the Saljūqs (1038-1194 CE).

480/1088 CE marks the beginning of a century-long recovery for Iraq—the ʿAbbāsid caliphs gradually manage to shake off the ‘‘protectorship” of the military (at this point, the Saljūq sulṭāns) and temporarily regain their independence. Caliphs, sulṭāns, and viziers (wazīr) vie for for influence with each other, seeking the support of religious scholars and relying on various mechanisms of promoting different legal schools—respectively, the Ḥanbalīs, the Ḥanafīs, and the Šāfiʿīs. The data from Taʾrīḫ al-islām shows that it is during this period that these groups start growing quite noticeably.

By the end of the period covered in Taʾrīḫ al-islām, Iraqi élites drastically decrease in numbers, practically disappearing from the social map of the Islamic world. Although the Mongol invasion is often considered the main cause, the data from Taʾrīḫ al-islām shows that the ranks of Iraqi élites start thinning well before the coming of the Mongols. Despite these vicissitudes, the number of notable men in Iraq remains quite significant over the most part of our period, and the prominence of Iraq is rivaled only by Iran, with all its clusters combined.

Major “middle bloomers,” Iranian provinces gain prominence between 100/719 CE and 200/816 CE. The curve of northeastern Iran (Ḫurāsān) reaches its highest point quite quickly around 200/816 CE and remains there, fluctuating slightly, for over three centuries, and goes into a rapid decline after 520/1127 CE. It takes longer for northwestern Iran to reach its peak—around 350/962 CE—and then it slowly goes down. Unlike northeastern Iran, it is still visible on the maps of the Islamic world by the end of our period. The curve of southwestern Iran reaches its highest point around 280/894 CE, then goes into a temporary decline during the 4th/10th century, recovers by 400/1010 CE and begins to go down slowly, increasing its pace of decline around 520/1127 CE. The major urban centers are: Nishapur/Naysābūr (1,038), Merv/Marw [al-šāhijān] (385), Herat/Harāŧ (392), Balkh/Balḫ (171) and Ṭūs (136) in northeastern Iran (Ḫurāsān); Rey/al-Rayy (280), Hamaḏān (254) and Qazwīn (118) in northwestern Iran; and Isfahan/Iṣbaḥān (1,124) and Šīrāz (100) in southwestern Iran.

The curves of Iranian clusters correspond to what scholars of Islam often refer to as ‘‘Iranian intermezzo”,2 a period of Iranian independent dynasties (roughly 750-1150 CE): the Ṭāhirids (821-873), Ṣaffārids (867-903) and Sāmānids (875-999) in the east and the Būyids (932-1055) in the north and west. All Iranian clusters practically come to naught by the end of the period covered in Taʾrīḫ al-islām.

The two-peaked curve of the last “middle bloomer,” al-Andalus, seems to correspond to the zenith of the Umayyad caliphate in Spain (756-1031 CE) around 380/991 CE, followed by its disintegration and the recovery under the Almoravids/al-Murābiṭūn (1056-1147 CE) and the Almohads/al-Muwaḥḥidūn (1130-1269 CE)—beginning around 470/1078 CE and peaking around 590/1195 CE; after that Andalusia is erased from the map of the Islamic world by the Christian Reconquista. The major Andalusian urban centers are Cordova/Qurṭubaŧ (633), Seville/Išbīliyyaŧ (248), Valencia/Balansiyyaŧ (141) and Toledo/Ṭulayṭilaŧ (89).

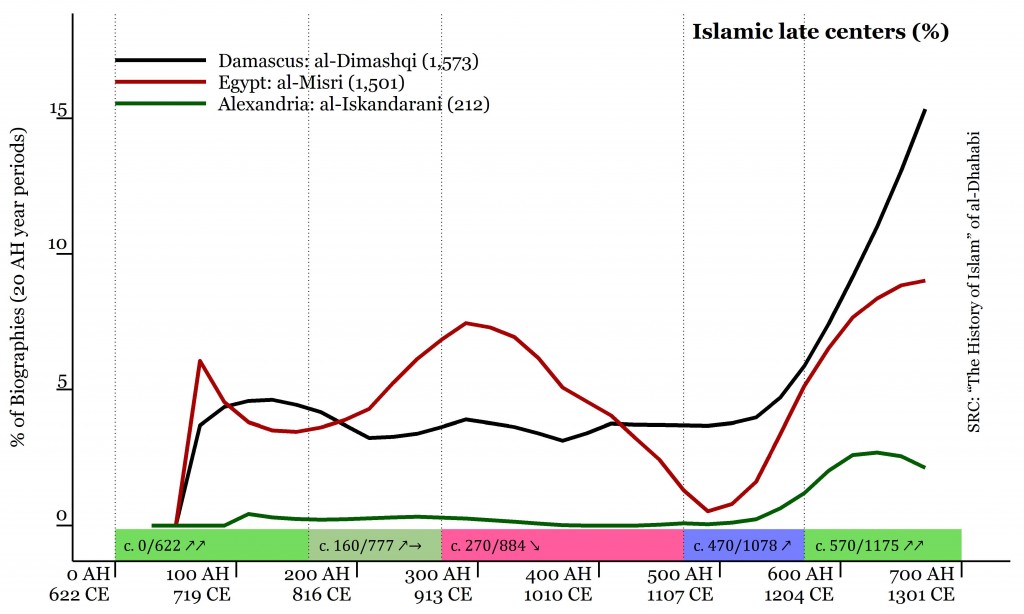

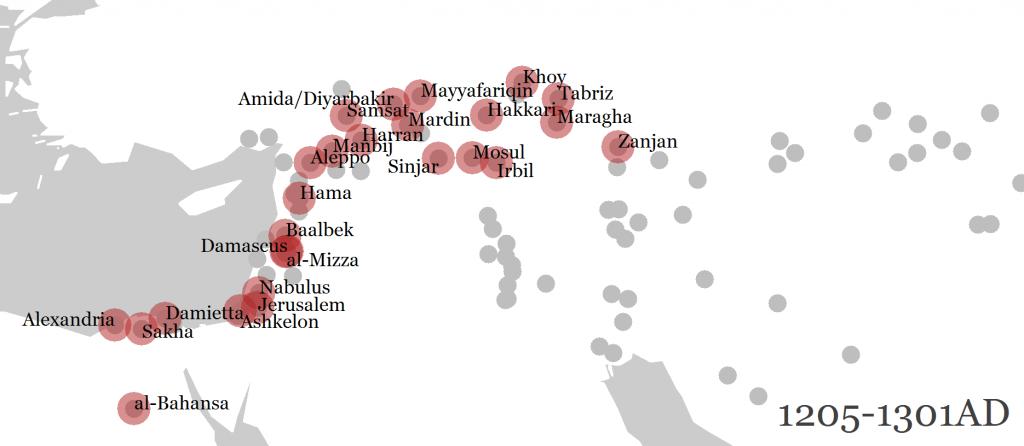

Regional clusters that can be characterized as “late bloomers” often have earlier peaks of prominence: around 100/719 CE for Syria, when the first great Islamic dynasty, the Umayyads (661-750 CE), rules from there; around 200/816 CE for the Jazīraŧ and Jordan; and around 300/913 CE for Egypt—followed by equally noticeable decline until around 500/1107 CE. However, their main peaks of prominence fall on the end of the period, by which the “late bloomers” form what can be considered as one continuous crescent-shaped macro-region stretching from Egypt/Miṣr in the south, through Jordan/al-Urdunn, Syria/al-Šām, the Jazīraŧ/Upper Mesopotamia, the northern part of Iraq, the very south of the Caucasian cluster in the north, and even touches northwestern Iran (Zanjān). The prominence of these regions rises noticeably after 500/1107 CE—right at the onset of the rule of dynasties that unify the region: the Zangids (1127-1222 CE), the Ayyūbids (1169-1250 CE), and the Mamlūks (1250-1517 CE). The major urban centers are: Mosul/al-Mawṣil (313) and Ḥarrān (224) in the Jazīraŧ; Damascus/Dimašq (1,769), Homs/Ḥimṣ (268), Aleppo/Ḥalab (231) and Hamah/Ḥamāŧ (103) in Syria; Jerusalem/al-Quds (315) in Jordan; and Alexandria/al-Iskandariyyaŧ (211) in Egypt/Miṣr.3 By the end of the main period covered in the Taʾrīḫ al-islām, Syria becomes the new center of the Islamic world, with Egypt being next in the line.

Cited Works

al-Ḏahabī (1990):

al-Ḏahabī. Taʾrīḫ al-islām wa-wafayāt al-mašāhīr wa-al-aʿlām. Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, Bayrūt, 2 edition, 1990.

Minorsky (1953):

Vladimir Minorsky. Studies in Caucasian History. CUP Archive, January 1953.

al-Samʿānī (1998):

al-Samʿānī. al-Ansāb. 5 vols. Bayrūt: Dār al-fikr, 1998.

Romanov (2013):

Maxim G. Romanov. Computational Reading of Arabic Biographical collections with Special reference to Preaching (661-1300 CE). Ph.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 2013.

Current Dataset

Sources: Taʾrīḫ al-islām of al-Ḏahabī (d. 748/1347)

Period: 41-700 AH / 661-1300 CE (Volumes 4-52)

Biographies: ~29,000

Unique Nisbaŧs: ~700

Total number of Nisbaŧs: over 70,000

Footnotes

- The nature of nisbaŧs is not unproblematic and anyone who has worked with biographical collections is likely to object saying that, for example, not every individual identified as “al-Madanī” was actually a Medinan; besides there definitely are Medinans who are not identified as such with this specific toponymic nisbaŧ, not to mention that the “descriptive name” al-Madanī (and its variation al-Madīnī) may refer to urban centers other than Medina. (See, for example, al-Samʿānī (1998), 5:235–239.) While such objections are not invalid, at this point of our knowledge and understanding of the overabundant biographical data from Arabic sources we simply do not know to what extent the presence of false positives (i.e., Madanīs who have nothing to do with Medina) and the absence of false negatives (i.e., the Medinans who are not identified as Madanīs) actually affects the overall picture. Working with big data requires some clearly identified methodological assumptions regarding the types of data used in modeling. My computational analysis of data from the Taʾrīḫ al-islām yields about 700 unique nisbaŧs (with over 300 toponymic ones) that identify at least 10 different individuals, while the overall number of these nisbaŧs runs into over 70,000 instances, considering that individuals are often described with more than one nisbaŧ. While 70,000 data points can hardly be called “big data” by any scientific standards, this dataset is too big to make exact identification of each and every nisbaŧ possible. Thus, under these circumstances, treating nisbaŧs at their face values is simply the most logical way to begin large scale analysis of biographical data from Arabic sources; as our knowledge about the “behavior” of nisbaŧs in biographical collections improves—and this can be achieved only through large-scale exploratory analysis—these methodological assumptions can and will be adjusted. For the detailed discussion of methodological assumptions see, Romanov (2013), 28–40. [↩]

- The term was introduced by Vladimir Minorsky (Minorsky (1953), 110-116). [↩]

- Cairo/al-Qāhiraŧ is not yet identifiable through onomastic data; most individuals from Egypt have the nisbaŧ al-Miṣrī (1,501) that associate them with the entire province. Although this nisbaŧ may also refer to Cairo, at the moment it does not appear possible to differentiate efficiently. [↩]