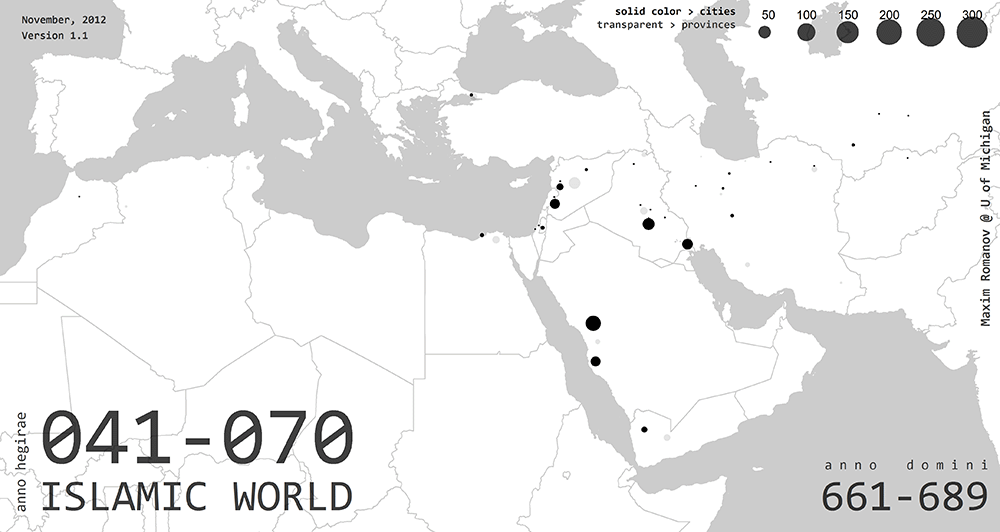

Islamic World, 661-1300 CE

Evenly spaced across the entire period of 41–700 AH/661–1300 CE, the following series of four maps (click to enlarge) visualizes the frequencies of top 100 toponyms mentioned in biographies of al-Ḏahabī’s Taʾrīḫ al-islām: almost 13,000 biographies (44,4%); altogether these locations are mentioned in slightly over 25,000 biographies. Only biographies that mention these places are been counted, i.e. if a certain place is mentioned several times in a specific biography it is counted only once.

The period of 41–70 AH/661–689 CE is the earliest three decades from the considered section of Taʾrīḫ al-islām. One can clearly see the major centers: Mecca/Makkaŧ, Medina/al-Madīnaŧ, Basra/al-Baṣraŧ, Kufa/al-Kūfaŧ and, to a lesser extent, Damascus/Dimašq. The empire grows eastward toward northern Iran and Central Asia, but cities in those regions are not prominent yet. This will change soon.

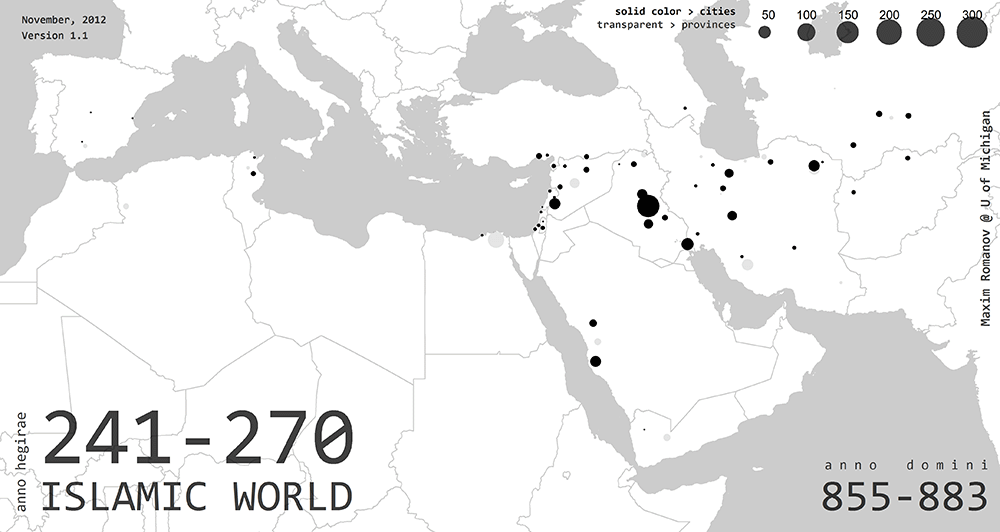

Two centuries later, 241–270 AH/855–883 CE, both northern Iran and Central Asia gain prominence. Greater Syria, al-Shām, is now more visible on the map of the Islamic world. Nothing significant seems to be going on in the Iberian Peninsula, the Maghreb and Egypt (Miṣr). Former centers—Medina/al-Madīnaŧ, Basra/al-Baṣraŧ and Kufa/al-Kūfaŧ—begin to loose their prominence; Mecca/Makkaŧ will suffer least because of its sacred status for the entire Islamic community. Yet, all the cities are dwarfed in comparison to Baghdad/Baġdād, the capital of the ʿAbbāsid caliphate which is about to plunge into the turmoil of disintegration. This disintegration seems to have significantly affected the numbers of notable people in al-Ḏahabī’s “History”—few decades later the number of biographies drops significantly and returns to its previous highest point only about two centuries later.

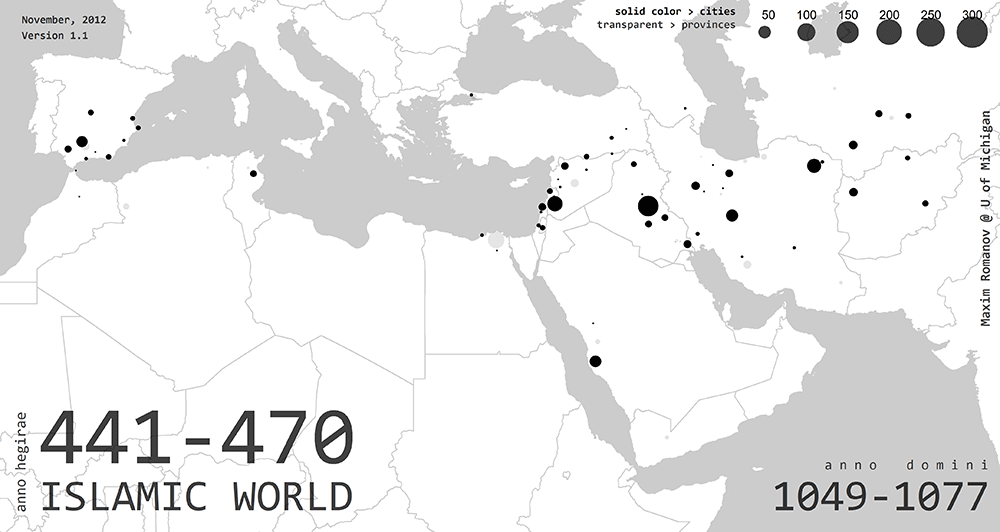

Two more centuries later, 441–470 AH/1049–1077 CE, Islamic Spain (al-Andalus) is clearly visible on the map. The western and northern parts of al-ʿAwāṣim—a region at the western part of the modern border between Turkey and Syria—are reconquered by the Byzantine Empire in the middle of the 10th century CE. The temporary capital of the ʿAbbāsid empire, Sāmarrāʾ practically disappears after the court is moved back to Baghdad/Baġdād. The rule of the Buyīds negatively affects Iraq, while most part of Iran, Central Asia and Afghanistan continue flourishing during this period of the rise of the Saljūqs.

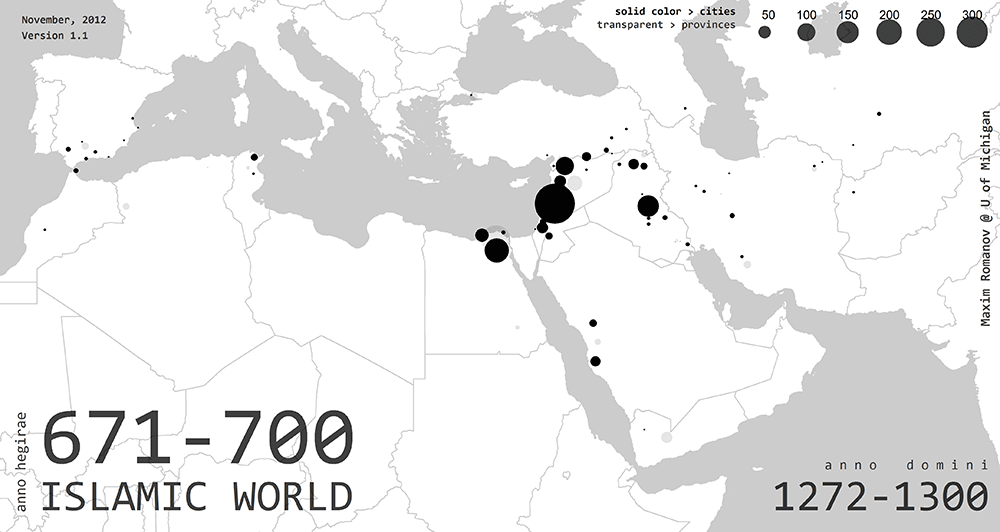

The end of the period, 671–700 AH/1272–1300 CE is drastically different. Spain is being erased from the map of the Islamic world by the ongoing Reconquista. Having flourished in the earlier periods, the eastern lands of the Muslim world—Iran, Central Asia and Afghanistan—fade away in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions. Still a prominent spot on the map, Baghdad/Baġdād will never recover from the Mongol sack of 1258 CE and by the last decade covered in Taʾrīḫ al-islām will shrink into a tiny dot. Consolidated under the Ayyūbids, Syria is now the seat of a new power—the Mamlūks, the saviors of the world from the Mongol menace. Under the Mamlūk rule, Egypt appears prominently on the map—with Cairo/al-Qāhiraŧ ready to become the next major center of the Islamic world.

The interpretation of these toponymic data is tricky and this explanation is just a preliminary attempt to weave them into a bigger picture. It is worth noting, however, that the toponymic data from Taʾrīḫal-islām is quite similar to the representation of the Islamic world in Šaḏarāt al-ḏahab of Ibn ʿImad (d. 1089/1679).1

Footnotes

- See, Graph I in: Bulliet, Richard W. Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979, p.8. Ibn ʿImad’s biographical collection covers the entire first millennium of Islamic history, but includes only ~8,500 biographies, of which only ~6,100 provide information on the places of origin of their subjects. Ibn ʿImad was also a Damascene, but he spent a lot of time in Cairo; unlike al-Ḏahabī, he belonged to the Ḥanbalī school of law. [↩]