Toward Abstract Models for Islamic History

NB: the paper has been presented @ Digital Humanities and Islamic & Middle Eastern Studies, Brown University, Providence, RI (October 24-25, 2013); the video recording of the presentation is available @ www.islamichumanities.org > Day One (timestamp of the presentation 2:48:00; Q&A: 3:51:30); the entire paper is also available as a PDF

All models are false, but some are useful

George P. Box

Why Models?

The advent of digital humanities has brought the notion of “big data” into the purview of humanistic inquiry. Humanists now have access to huge corpora that open research possibilities that were unthinkable a decade or two ago. However, working with corpora requires a rather different approach that is more characteristic of sciences than humanities. Namely, one has to be transparent and explicit with regard to how data are extracted and how they are analyzed. Text-mining techniques rely on explicit algorithms because they help tracing mistakes, correcting them and, ultimately, improving results.1 Analytical procedures for studying extracted data rest on explicit algorithms for the same reason. As a way of constructing algorithms, modeling is part and parcel of developing complex computational procedures.

Working with big data also requires a different kind of modeling. Opting for the breadth of data we have to give up the richness of details. Close reading—to which humanists are most accustomed—becomes impossible.2 Working with big data one cannot maintain the nuanced complexity of details that became the hallmark of close reading as an approach. Instead of relying on complex textual evidence and reading between the lines one has to work with relatively simple textual markers—essentially, words or simple phrases—that are treated as indicators of large trends. Yet, it is through such analysis that we can look into long-term and large-scale processes that will always remain beyond the scope of close reading. The literary historian Franco Moretti dubbed such an approach “distant reading, ” explaining distance” not as an obstacle, but a specific form of knowledge.3 With emphasis on fewer elements that allows us to get a sharper sense of their overall interconnection, we can distinguish shapes, relations, structures. Most importantly, we can trace small changes over long periods of time.

Modeling is an important part of this approach. With models we simplify reality down to a limited number of factors4 through the analysis of which we hope to get insights into complex processes.5 This simplification is the reason why all models are false. Yet, models are a valuable and powerful tool. They pave the way to improving our understanding of the world. Unlike theories, models are experimental and driven by data. Good models offer invaluable glimpses into the subjects of our inquiry.6 With them we can explore, explain, project. With them we can get a big picture. That is why some models are useful.

What follows is an attempt to model Islamic élites based on the data from al-Ḏahabī’s (d. 748/1348 CE) Taʾrīḫ al-islām in order to explore major social transformations that the Muslim community underwent in the course of almost seven centuries of its history. The main types of data used in the model are dates, toponyms,7 linguistic formulae (or, wording patterns), synsets (lists of words that point to a specific concept or entity), and, most importantly, “descriptive names” (sing. nisbaŧ).

The detailed discussion of main assumptions regarding these types of data as well as the discussion of such general issues relevant to the study of Arabic biographical collections can be found elsewhere.8 Here it is most important to dwell on our assumptions regarding “descriptive names” that are regarded by some scholars as the most valuable kind of data that literary sources offer to the social historian of the Islamic world, and by others as highly problematic as such. The major problem with nisbaŧs is that it is not always clear what they stand for. For example, if an individual is described in a biographical collection as ṣaffār, does this actually mean that he was involved in “copper smithing”? When our subject is just one particular individual, it is not so difficult to establish the more or less exact meaning of this descriptive name by cross-examining biographies of this individual in other biographical collections. This is particularly easy now when dozens of electronic texts of biographical collections are just few mouse-clicks away. However, such an approach becomes problematic when this rather time-consuming procedure has to be repeated for dozens of individuals. The approach becomes particularly difficult if our goal is to study some biographical collection in its entirety, since Arabic biographical collections often contain thousands of biographies and most biographies offer multiple descriptive names for the same individual. After a certain threshold it becomes impossible to apply this approach at all. Our source, Taʾrīḫ al-islām, is well beyond this threshold. In the analysis that will follow, we will deal with the dataset of almost 70,000 nisbaŧs (with about 700 unique ones) that represent about 26,000 individuals over the period of 41–700/1301 CE. Working with such a dataset one cannot possibly know the exact meaning of each and every nisbaŧ. At the same time we do not have any solid foundation to argue that descriptive names are to be treated in a particular manner, or to be discarded altogether. Yet, such a dataset is too unique an opportunity for research to ignore simply because we are not entirely sure what all these data mean. This is where modeling offers an optimal solution: we need to start with assumptions and be upfront about them. In what follows, descriptive names will be treated at their face value, if only because this is the most logical starting point.9

The Source: al-Ḏahabī’s Taʾrīḫ al-islām

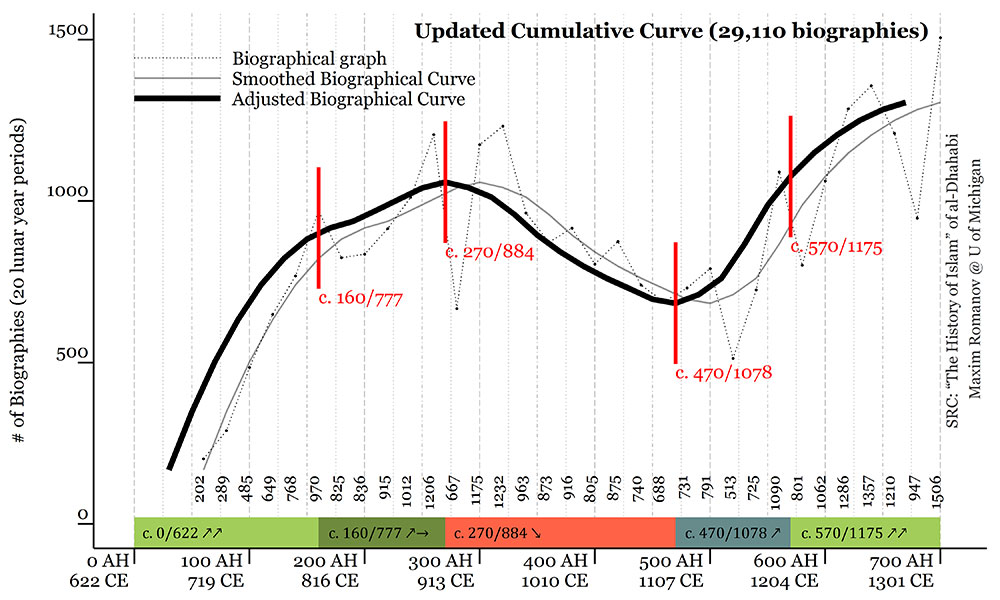

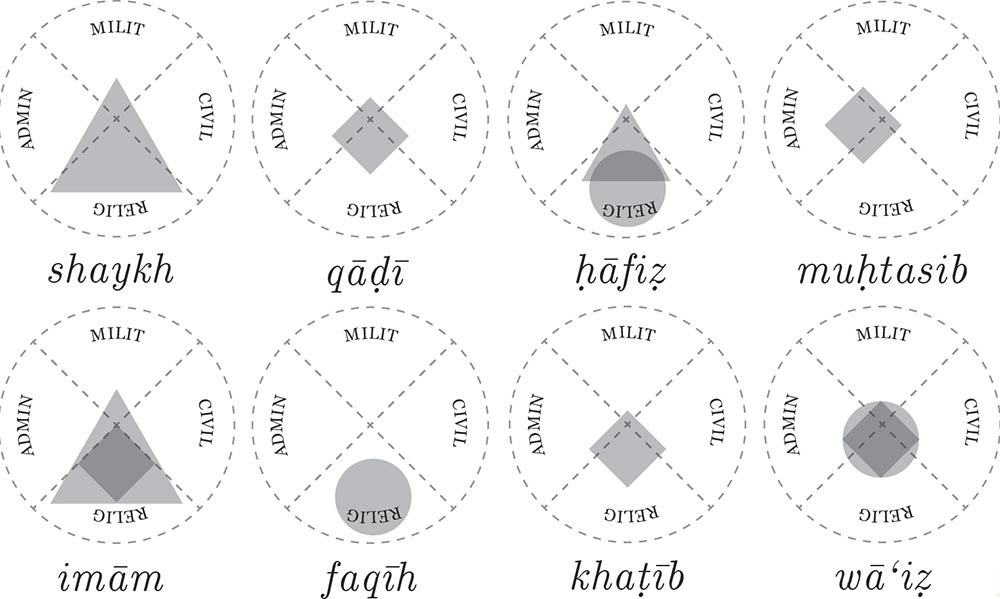

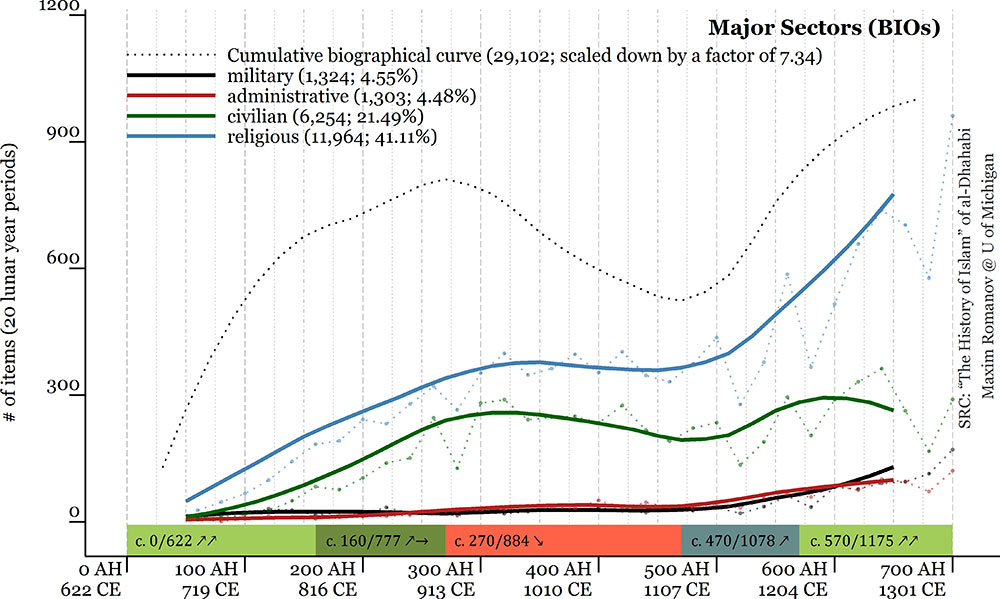

Taʾrīḫ al-islām is the largest Arabic biographical collection that includes over 30, 000 biographies and covers almost seven centuries of Islamic history. The current dataset includes information on slightly over 29, 000 individuals (the first three volumes of Taʾrīḫ al-islām are structured differently from the rest of the collection and cannot be studied with the same computational method). Figure 1 shows cumulative biographical graphs and curves based on this data set. Biographies are grouped into 20 lunar year periods (quantities of biographies for each period are shown at the bottom of the Biographical graph). The graph is transformed into a curve that smooths out the noise of data, emphasizing larger trends (Smoothed Biographical Curve). Finally, the main curve is the Adjusted Biographical Curve, which is shifted 30 years back in time to reflect “the years of floruit” of the biographees from Taʾrīḫ al-islām.

The curve can be split into several periods, each beginning at a point that marks a noticeable diversion of the curve. The number of biographies keeps on growing quite rapidly until c. 160/778 CE, which marks the slowing of growth. During c. 270-470 AH/884-1078 CE there is a steady decline. After c. 470/1078 CE the curve starts recovering, reaching its highest point around c. 570/1175 CE, after which it keeps on growing, but slows its pace by the end of the period—with the second peak being somewhere after 700/1301 CE. For convenience, many of the graphs that will follow will include the scaled-down cumulative curve and color-coded periods.

Modeling Society

The individuals whose lives are described in biographical collections were not ordinary people. They were integrated into the life of society to a noticeable degree—somewhere on the scale from noteworthy to extraordinary. Almost every biographical note contains some information on a sphere of life to which its protagonist contributed—and “descriptive names” is the most manageable indicator of this.

Major studies that use “descriptive names” for analytical purposes split them into categories. Cohen’s classic study10 concentrates primarily on “secular occupations” during the first four centuries of Islamic history. He offered a major division of occupational nisbaŧs (textiles, foods, ornaments/perfumes, paper/books, leather/metals/wood/clay, miscellaneous trades, general merchants, bankers/middlemen) and supplied an extensive appendix with explanations for about 400 nisbaŧs and relevant linguistic formulae. Unfortunately, the nisbaŧs in Cohen’s appendix are not explicitly categorized and—since any categorization involves pushing the boundaries, especially in instances that stubbornly resist classification—the exact scheme remains somewhat unclear.

Petry’s scheme is built on biographical data from Mamlūk Egypt (1258–1517 CE). Petry divided his subjects into six major, often overlapping occupational groups: executive and military professions, bureaucratic (secretarial-financial) professions, legal professions, artisan and commercial professions, scholarly and educational professions, and religious functionaries. Although explicit classification is not given in the “Glossary of Occupational Terms, ” numerous tables provide enough information to form a rather clear idea about the specifics of each category in Petry’s classification scheme.11

Shatzmiller approached this issue from the much wider perspective of labor in general. Her scheme covers a much wider variety of occupational names and splits the entire society into three major sectors—extractive, manufacturing, services—with each sector having its overlapping subcategories. Schatzmiller offers an explicit categorization of each and every descriptive name.12

As is the case with any scheme, all three examples are designed to serve specific purposes. Although immensely helpful, none of them are suitable for the purposes of broader analysis: unlike the above-mentioned schemes, the scheme needed here must take into account all meaningful descriptors, not only those that can be classified as “occupations.” In other words, it must consider anything that would allow discerning all potentially identifiable groups so that their evolution could be traced. Some of these descriptors do not pose significant problems, others are so complex that even presenting them as ideal types might be highly problematic.

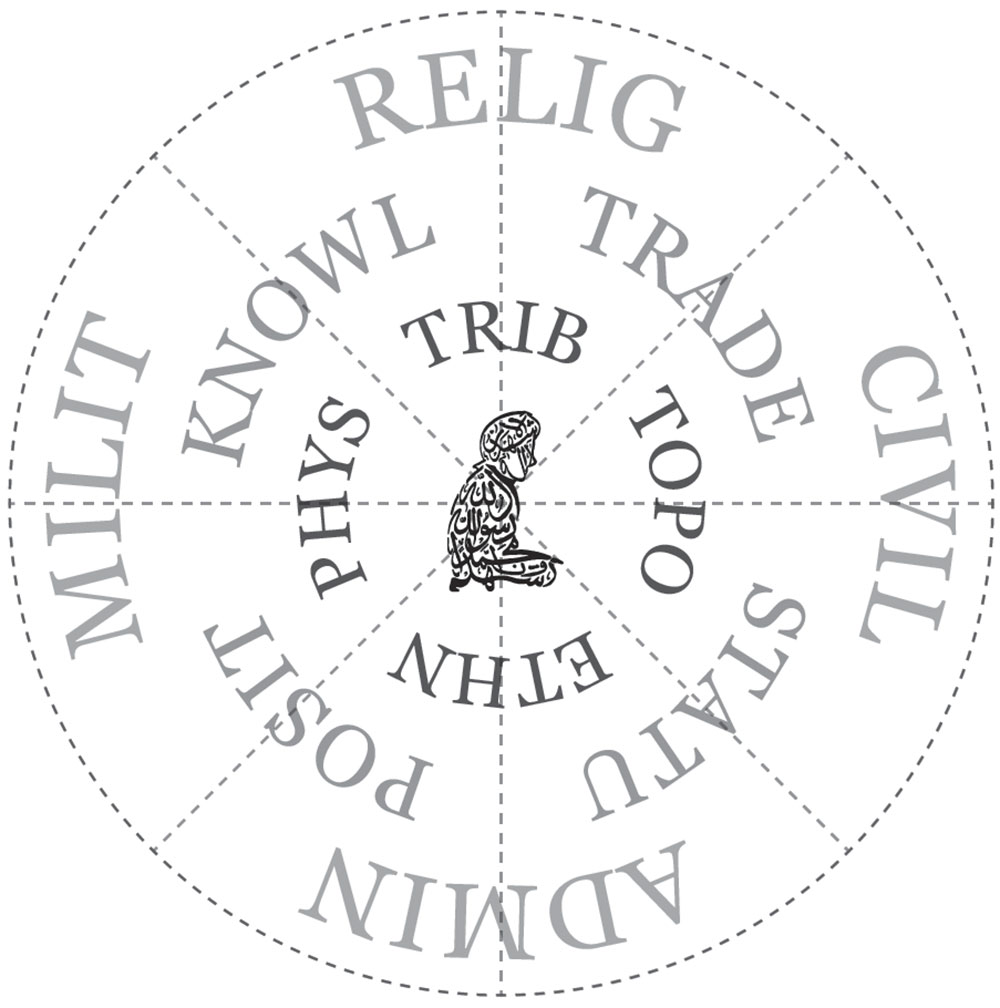

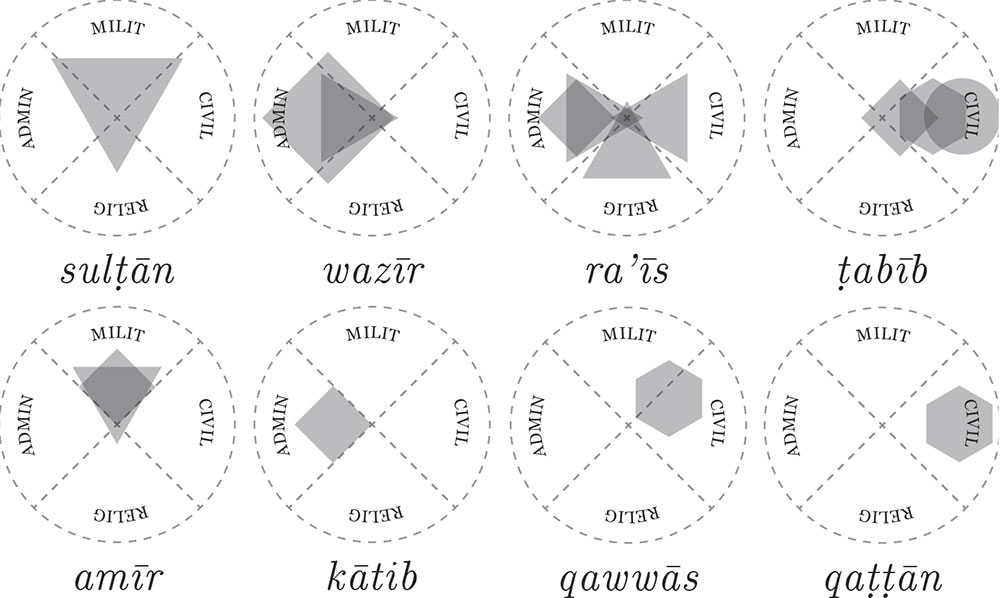

The list of “descriptive names” from Taʾrīḫ al-islām is based on frequencies and for the moment I consider nisbaŧs that are used to qualify at least ten individuals (slightly over 700 unique nisbaŧs, with their total running up to almost 70,000 instances). My list of descriptive names overlaps only partially with those of Cohen, Petry and Shatzmiller. Figure 2 shows how the categories of “descriptive names” from Taʾrīḫ al-islām are interconnected from the individual perspective.

The innermost layer of categories includes tribal, toponymic, ethnic and physical descriptions. These are descriptors over which individuals have the least control—in a sense that no one chooses into which tribe to be born, where to be born, what ethnic group to belong to, and what physical peculiarities to have or suffer from. To a certain degree these description are also acquirable—in the early period being a Muslim meant being affiliated with an Arab tribe; individuals were constantly moving around the Islamic world, changing their toponymic affiliations; physical peculiarities could have resulted from life experience. However, these are only probable—and thus secondary—cases that would usually be piled up on top of primary, “by-birth” descriptions. The first three categories—tribal, toponymic, ethnic—also tend to overlap.

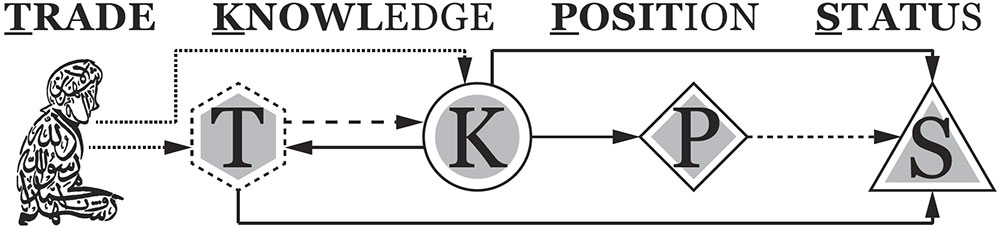

The middle layer groups “descriptive names” in terms of acquirable qualities—trade, knowledge, positition and status. These are not categories that rest on the same level and their connections are better represented in an hierarchical manner (Figure 3). The main gateways to élites were trades (or “secular occupations”) and knowledge[s]. However, practicing some trade alone was almost never enough: biographical collections rarely—if ever—include individuals who were involved exclusively in some specific “secular occupation.” In order to climb up the social ladder a practitioner of any trade had to start converting his economic capital into social—this was most commonly done through acquiring religious knowledge. Knowledge—as specialized training in a specific area that would set an individual aside from the masses—opened ways for acquiring positions and status[es]; it could also allow one to practice trade on a new level, thus improving individual’s status.

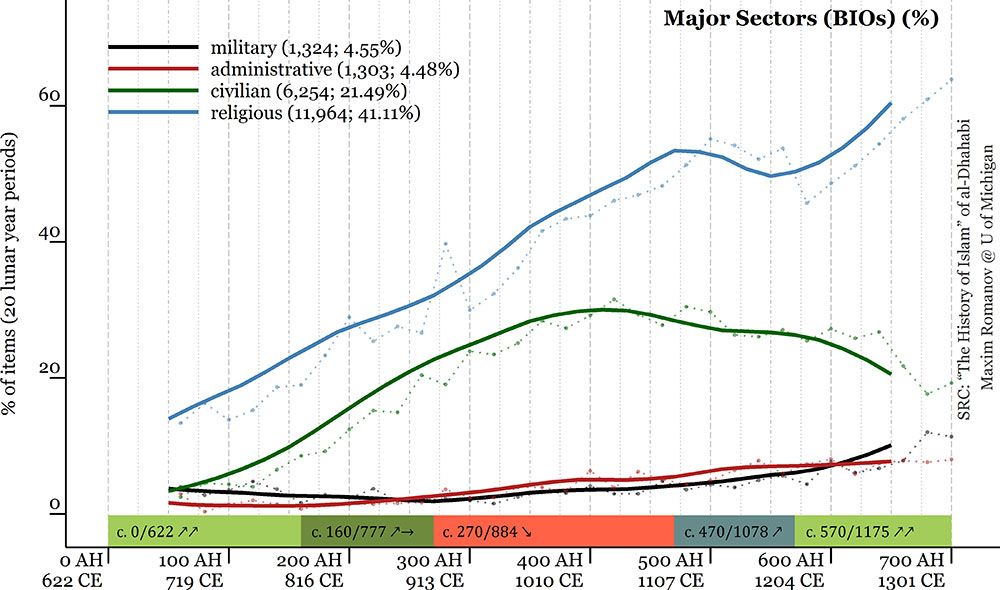

The outermost layer represents the major sectors to which a person could belong in pre-modern Islamic society: religious, administrative, military, and “civilian.” The term “civilian” is problematic, and is used here essentially as a negative blanket category that encompasses everything that does not clearly belong to the first three sectors. Descriptive names often cross boundaries among these categories and most individuals do not clearly belong to one specific sector, but rather balance among them.

For our purposes it will be more efficient to invert this scheme so that “descriptive names” are presented from the social perspective (Figure 4). Now, each category contributes to the composition of Islamic society, and every “descriptive name” can be seen as a social role. These roles are likely to receive a centripetal charge from individuals who attempt to expand their influence on society at large; how close they get to the center—i.e., how much social influence they can exercise—would depend on the success of particular individuals and/or historical circumstances that might be favorable to particular groups. Social influence here is understood broadly as a pressure that forces someone to do something that s/he otherwise would not have done; at this point I do not make a distinction between physical threats and social pressures. Clearly, the sword of an amīr, “military commander, ” and the word of a šayḫ, “religious authority, ” are different in their nature, but both may have equally serious societal consequences.

Figures 5 & 6 should provide a visual clue to how these overlapping categories are used in the classification scheme. On Figure 5: amīr, “governor, commander, ” and sulṭān, “sultan, ” both belong to the military sector of society. Amīr can be seen primarily as a position—in a sense that there is somebody above who granted this position to a given individual; arguably, this position provides one with a relatively high status. Sulṭān is the apex of the military hierarchy and thus is primarily seen as status with significant influence over all other sectors. Kātib, “scribe, ” and wazīr, “vizier, prime minister, ” belong to the administrative sector, where the former is a position with potential for social influence, while the latter is the apex of the administrative hierarchy, which gives one significant resources to influence society at large—hence, it is also status.13 Somewhat an equivalent to amīr, raʾīs, “chief, director, ” is a denomination of high status in either the civilian, the religious or the administrative sector (also position in the latter). Ṭabīb, “physician, ” stands for special training—knowledge—within the civilian sector, which is also likely to fall into the categories of trade and position, especially after hospitals (sing. bimaristān) become a constant element of the Muslim cityscape.14 Qaṭṭān, “producer or seller of cotton, ” and qawwās, “bow-maker, ” are both secular occupations—trades—and thus belong to the civilian sector, although the latter—if bows are produced for war-making purposes—may cross into the military one.

On Figure 6: Šayḫ, literally “elder, ” and imām, “leader, ” are the markers of the highest religious status, although in the later period imām also refers to a religious position of “prayer leader” that was only marginally influential in social terms. Faqīh refers to knowledge of Islamic law, whereas social influence is exerted primarily through other roles, such as qāḍī, “judge, ” which is always a position—or muftī, “juristconsult, ” which turns into a position in the later period (not graphed). Ḥāfiẓ denotes knowledge of Prophetic tradition and high achievement (status) within this area of religious expertise. Muḥtasib, “market inspector, ” is an administrative position with strong religious underpinnings. Last on the list are ḫaṭīb, “Friday preacher, ” and wāʿiẓ, “public preacher.” Both belong to the religious sector, but while the former is always a position, the latter refers to a specific field of religious knowledge that tends to become a position only during the later period.

Individuals in the Islamic biographical dictionaries usually wear many turbans and are qualified with more than one “descriptive name.” Using the same method, each individual can be represented as a unique constellation of trades, knowledge[s], positions and status[es] that are fitted into the diagram of the four major sectors. Pushing this approach even further, we may try to evaluate how the composition of Islamic élites—and, possibly, society at large—changed over time, although conventional graphs may be more efficient for this task.

Looking into Major Sectors

Introducing the categories of sectors—military, administrative, religious and civilian—I hope to use them as markers of change within the composition of Islamic élites. Society would remain healthier when more social groups are represented in the élites, since a more diverse population will be participating in the [re]negotiation of the rules of the game. This is what the share and the diversity of the civilian sector—with a number of trades, crafts and knowledge[s]—is meant to represent.

Figure 7 shows the cumulative curves of all four sectors. Although this is still work in progress and algorithms for determining the administrative and military sectors still need adjustment, the curves do agree with the major trends that we expect to be confirmed by quantitative analysis.

The religious sector keeps on growing throughout the period. Occasional fluctuations notwithstanding, it hits the 60% mark by the end of the period. One would expect this number to be higher, but a significant number of individuals participated in the transmission of knowledge without specializing in specific fields of religious learning and thus did not not earn relevant nisbaŧs. This, of course, may result from irregularities in naming practices or the lack of verbal patterns in my synsets.

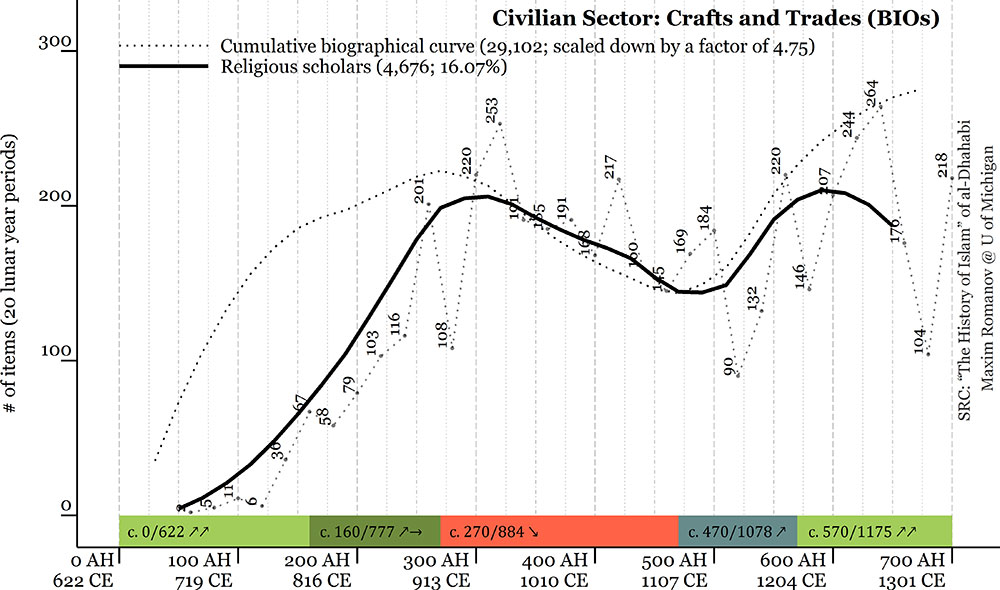

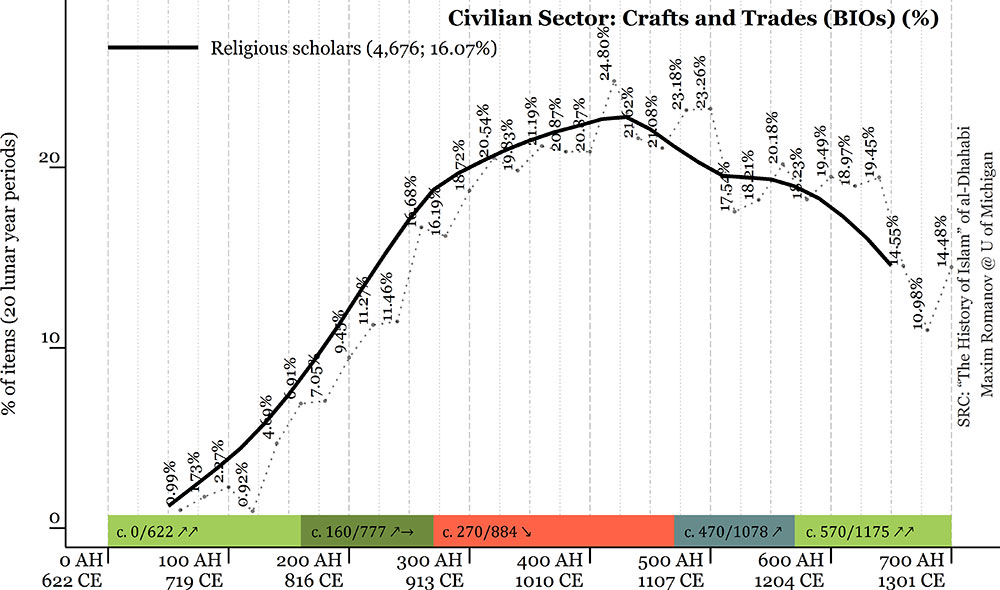

The civilian sector is at its highest during 300-400 AH/913-1010 CE, when it reaches a 30% share. By the end of the period it goes down to 20%. The number of individuals involved in trades and crafts is about 24-25% at its highest point around 400/1010 CE and goes down to 13-14% by the end of the period.

The administrative and military sectors are not as significant in terms of numbers, but the representatives of these sectors are in better positions to make the most immediate and most striking impact on society at large. Both sectors keep on growing, although while the growth of the administrative sector is constant, albeit rather slow, the growth of the military sector is quite remarkable, especially after 500/1107 CE. Overall, the share of the military sector could have been reaching up to 10% during the later periods, which is very significant considering that at some earlier periods this sector is lacking altogether. The administrative sector may have hit the mark of about 8% during the later periods.

Major Social Transformations

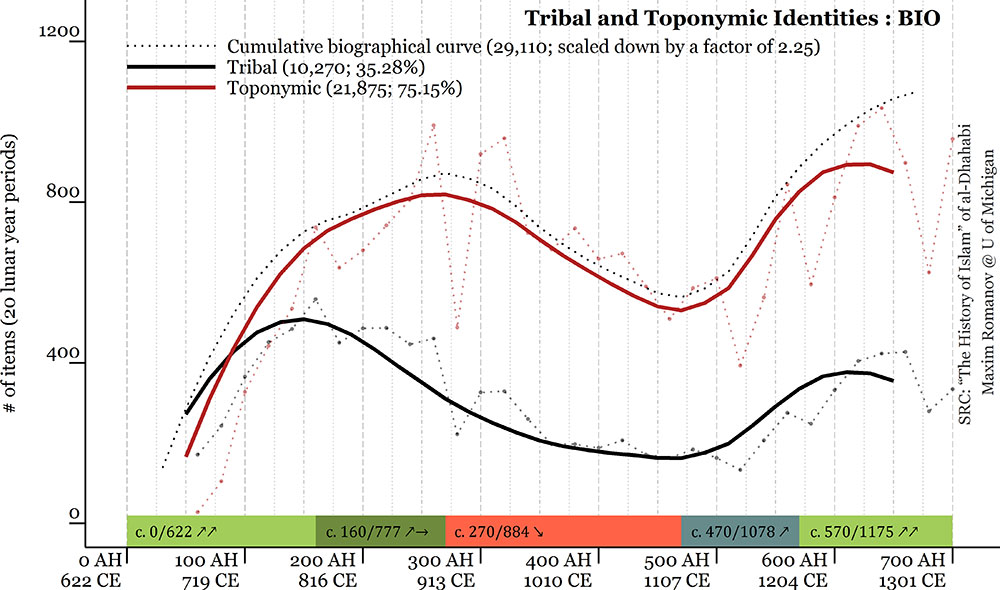

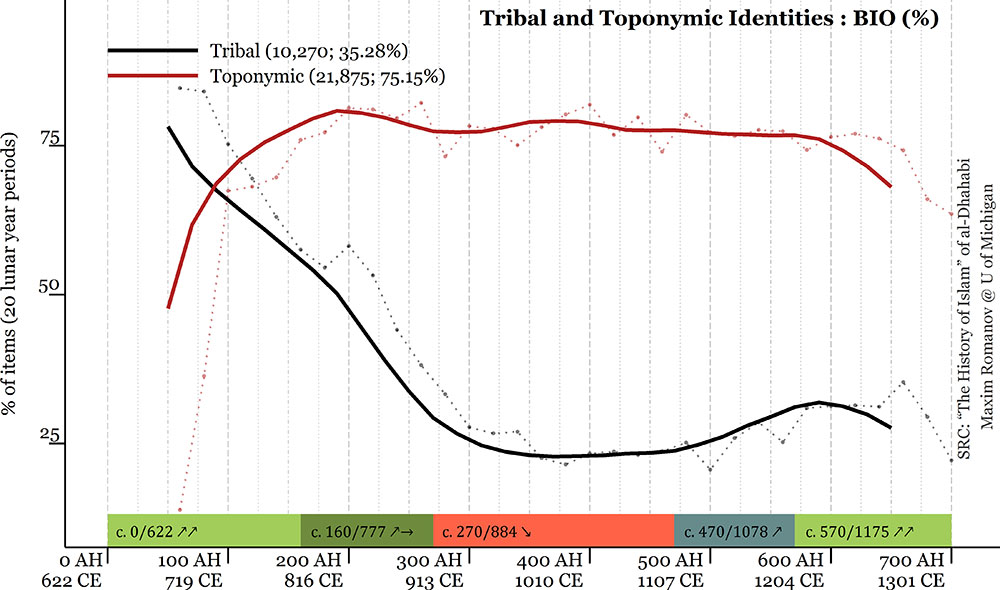

De-tribalization is one of the most striking processes that the onomastic data show. Islamic society starts as a tribal society with up to 85% of individuals in the earliest periods qualified through tribal affiliations. As the Islamic community grows and spreads over the Middle East and North Africa, the number of individuals with tribal identities rapidly goes down (Figure 8) and by about 350/962 CE only 20–25% of the individuals in the Taʾrīḫ al-islām have tribal affiliations. From this point on—perhaps even earlier—tribal affiliations persevere in different capacities: some as dynastic (most prominently, the nisbaŧ al-Umawī that spikes again after 350/962 CE in Andalusia), but in most cases as status markers.

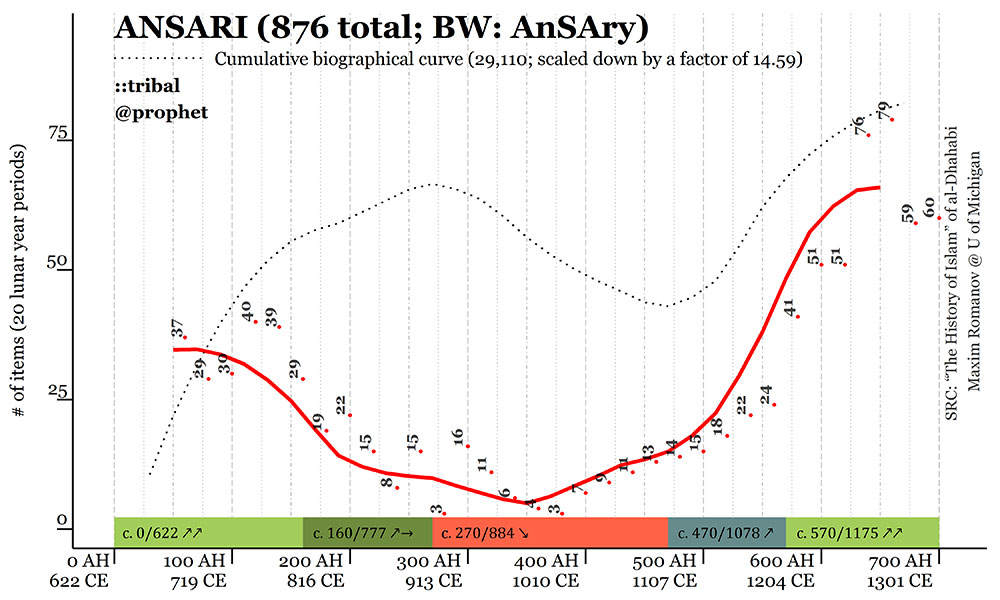

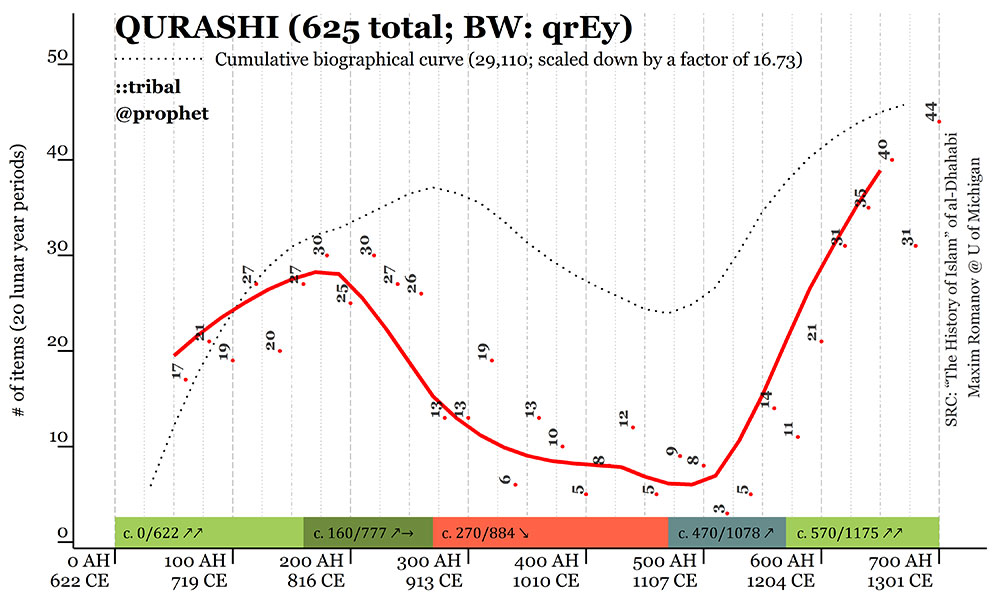

Such nisbaŧs as al-Anṣārī (Figure 9) and al-Qurašī (Figure 10) make quite a noticeable comeback. The numbers of al-Anṣārīs (this nisbaŧ is particularly frequent in Andalusia as well) begin to grow quite rapidly after 350/962 CE and the number of al-Qurašīs practically skyrockets right after 500/1107 CE. However, even though their absolute numbers are much higher in the later periods, their percentages never reach their early peaks: the highest peak of al-Anṣārīs in the earliest periods is 18.32%, while the highest one in the later periods is only 6.53%; with al-Qurašīs these numbers are 8.42% and 3.31%. Some other tribal nisbaŧs are re-claimed as well, but the overall number of individuals with names that associate them with Arab tribes remains rather low, only briefly going above the 30% mark.

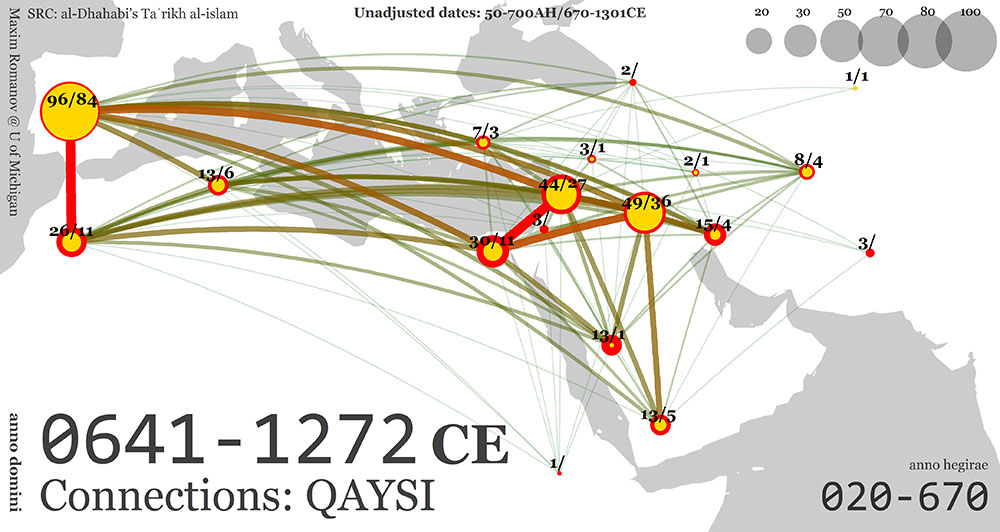

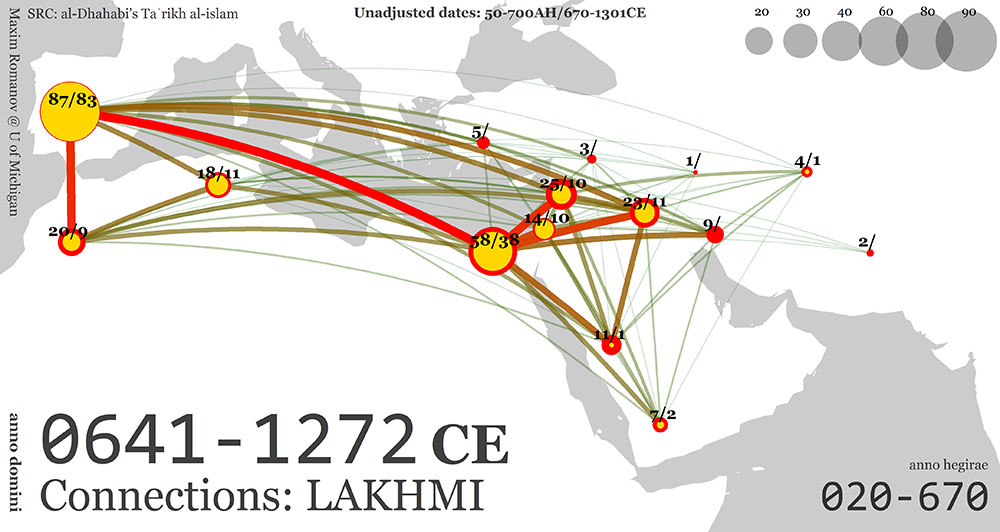

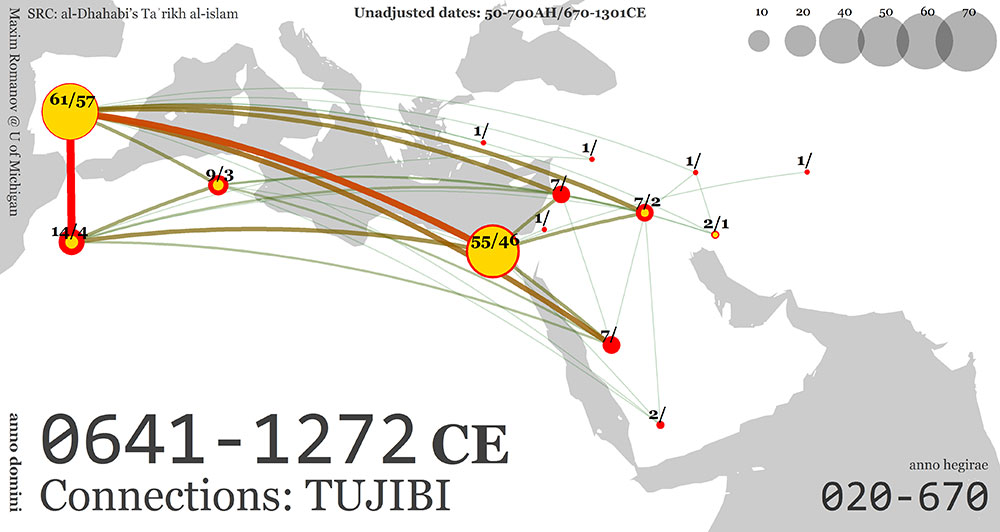

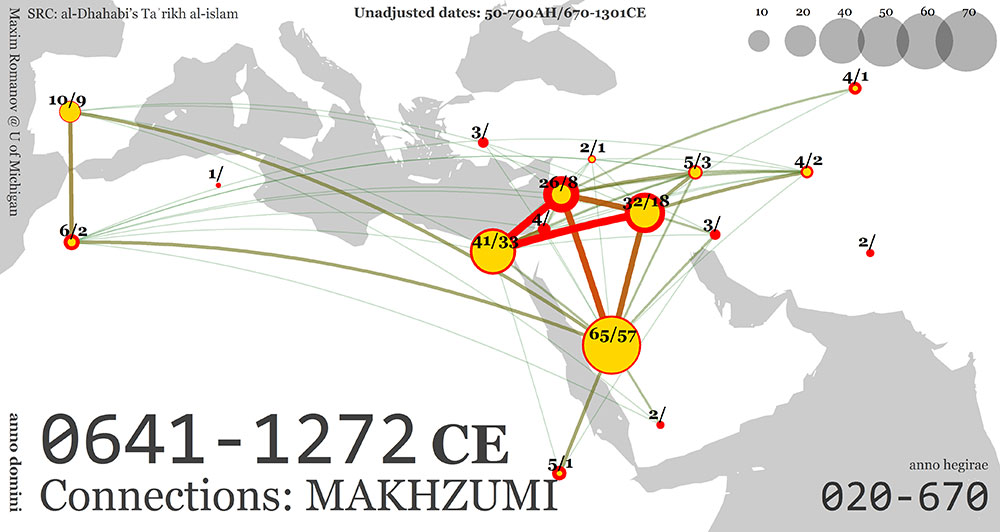

Most tribal nisbaŧs display rather distinctive orientations toward the East or the West of the Islamic world. “Late bloomers” are most often oriented toward the West (Figure 11). For example, such nisbaŧs as al-Qaysī (208) and al-Laḫmī (183) feature most prominently in Andalusia (84 al-Qaysīs and 83 al-Laḫmīs); al-Tujībī (127)—in Andalusia (57) and Egypt (46); al-Maḫzūmī (182)—in Egypt (33);15 al-Saʿdī (191)—in Egypt (50) and Syria (25). But again, the percentages of “late bloomers” never reach those of the earlier periods.

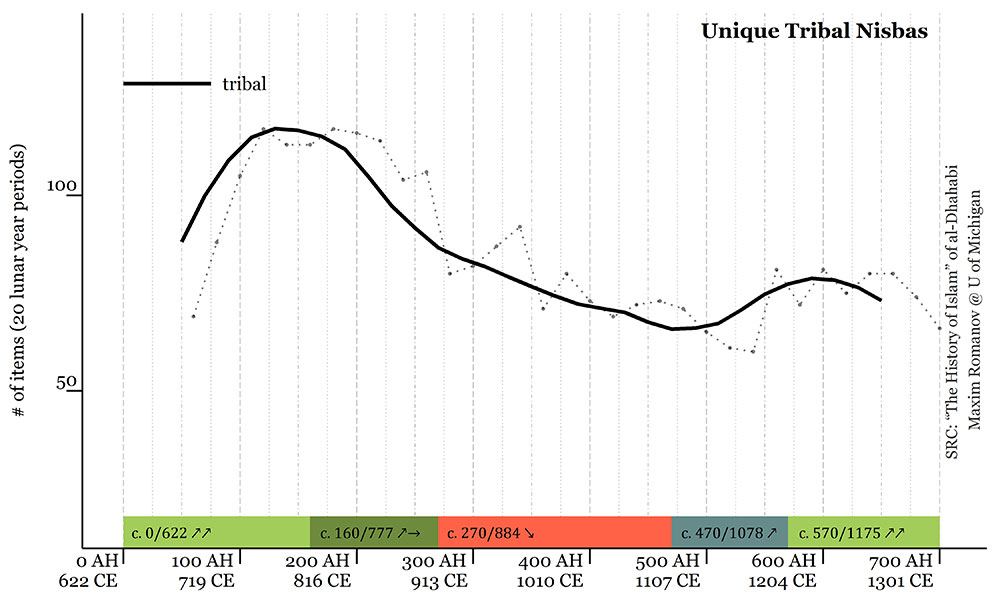

The change in tribal identities can also be seen through the numbers of unique tribal nisbaŧs per period (Figure 12). In general, they display a similar trend. At its highest the number of unique tribal nisbaŧs fluctuates at around 115 during the period 100-200 AH/719-816 CE. It drops to about 60 by 500/1107 CE and then grows back to about 80—most likely through the re-appropriation of old tribal nisbaŧs that are now used as status markers as well as through the introduction of Turkic and Kurdish tribal identities—but by the end of the main period this number goes down to the 60–70 range.

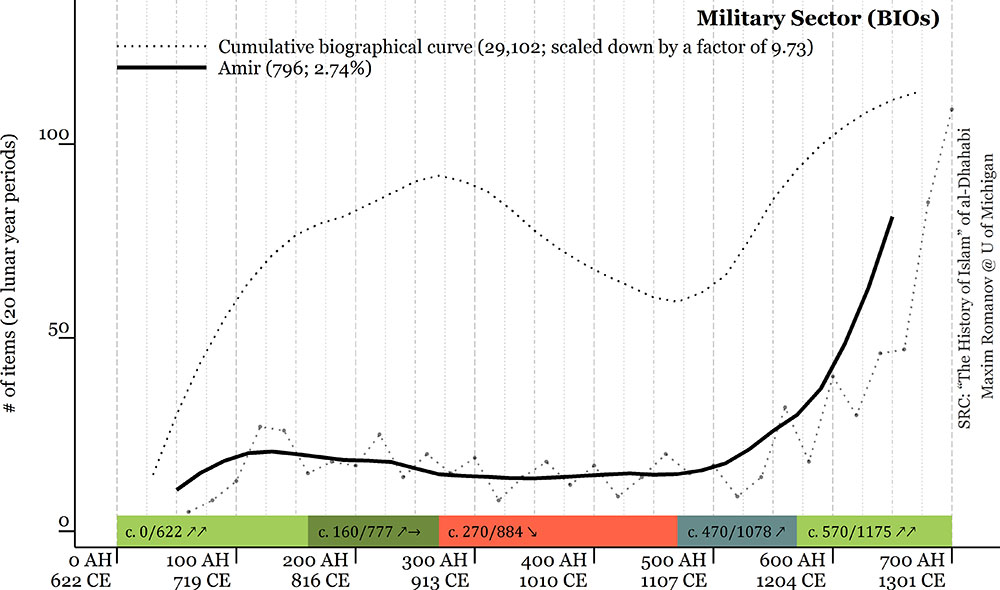

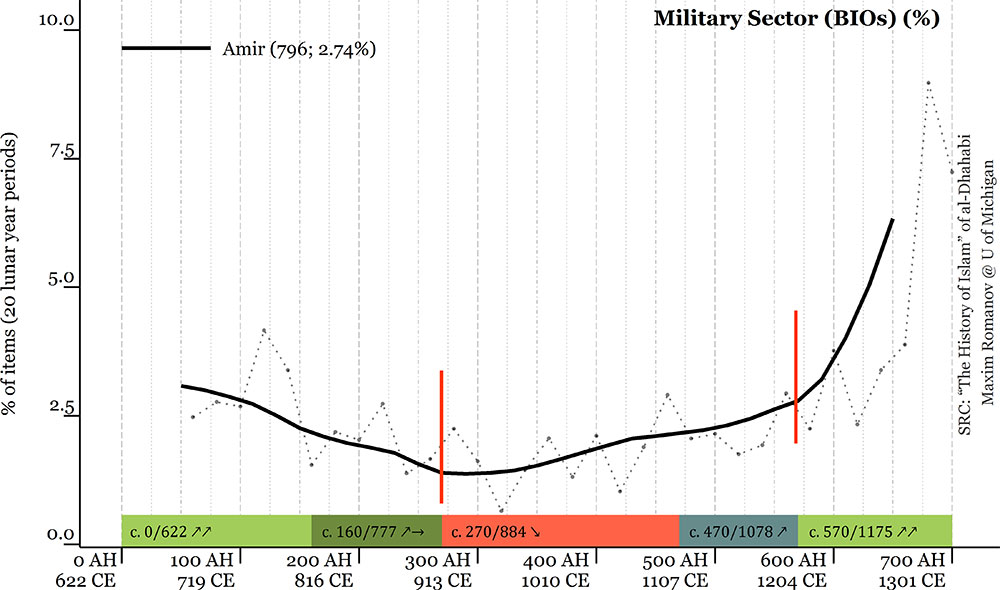

Militarization. Onomastic data from Taʾrīḫ al-islām allows us to take a closer look at the process characterized by Hodgson as “perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Middle Islamic periods.”16 The absolute numbers on Figure 13 (left) show that the military sector of élites begins to grow rapidly after 500/1107 CE—the numbers of amīrs included in the Taʾrīḫ al-islām are staggering.17 Geographically, this spike of militarization is clearly visible in Iraq, the Jazīraŧ, Egypt, but in Syria more than anywhere.

The relative numbers in Figure 13 (right) allow for a more detailed glimpse into how the military were treated by the learned class who composed biographical collections that became sources of al-Ḏahabī’s “History.” And the percentages tell a somewhat different story. Interestingly, the turning points of the military curve coincide with those of the cumulative biographical curve. The military curve, however, has three clearly visible sections, or periods. The first section, the early period up until 270/884 CE, shows the decline of the military in Islamic society. This process of de-militarization went on hand-in-hand with de-tribalization, during which the diversity of the Islamic community grew, the ethos changed and swords and horses were exchanged for pens and donkeys. 270/884 CE is the first peak of the cumulative biographical curve: the highest percentage of the learned and the lowest percentage of the military in the Taʾrīḫ al-islām.

During the middle period of 270-570 AH/884-1175 CE, when the cumulative biographical curve takes a dive and then, after 470/1078 CE, begins to recover, the share of the military in Taʾrīḫ al-islām grows slowly. This can be marked as the beginning of [re-]militarization of Islamic élites. Unlike in the early period, however, now the amīrs are not Arab[ian] warriors, but Turkic military commanders.

After 570/1175 CE—when the cumulative curve recovers and continues growing further—the percentage of military commanders in the élites begins to grow as rapidly as their absolute numbers. This third period shows a successful integration of the military into the élites and the their numbers strongly suggest that religious scholars take even minor commanders seriously.

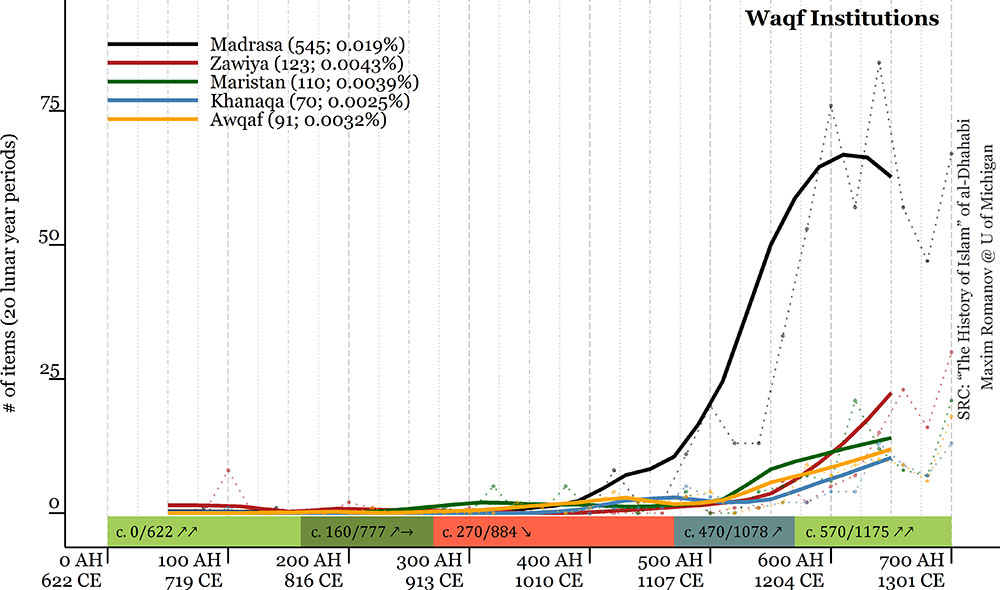

Military commanders do a lot to make a place for themselves in the dense social space of the Islamic society: as their biographies show, they build madrasaŧs, hospitals (bimāristān) and establish other waqf institutions. More and more often they participate in the transmission of knowledge, which scholars report.

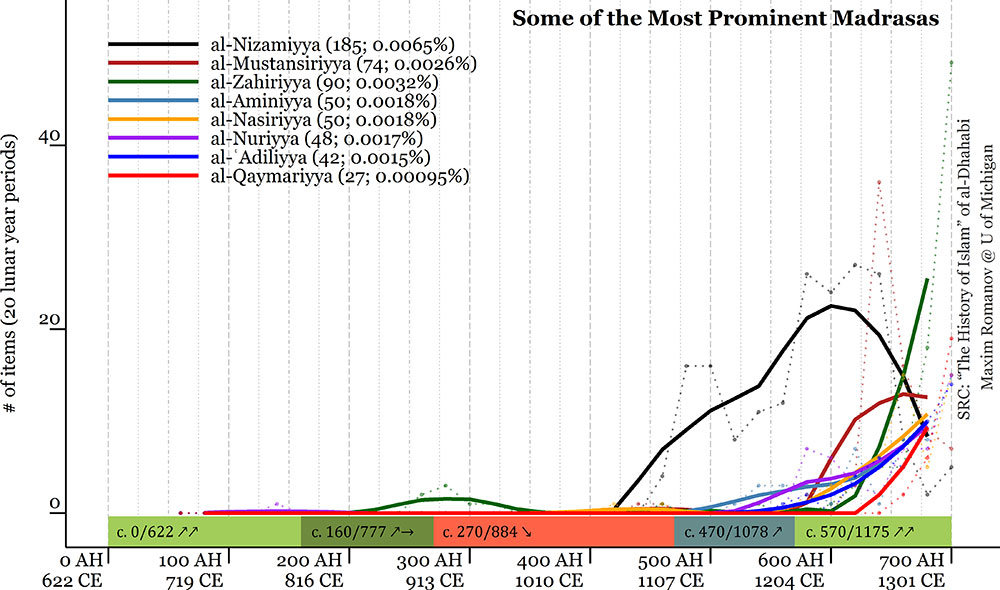

The military—the amīrs themselves and members of their families18—are not the only ones building madrasaŧs and, judging by the frequencies of their mentions, their establishments are not the most prominent. However, they definitely compensate for this in numbers: there are significantly more endowments established by the military than by members of other groups.19 Figure 14 shows the curves of the most frequently mentioned madrasaŧs in Taʾrīḫ al-islām. The vizieral al-Niẓāmīyaŧs and the caliphal al-Mustanṣirīyaŧ feature more prominently. However, their curves strongly suggest that their prime time is over, while “military” madrasaŧs—al-Ẓāhirīyaŧ, al-Amīnīyaŧ, al-Nāṣirīyaŧ, al-Nūrīyaŧ, al-ʿĀdilīyaŧ and al-Qaymarīyaŧ and others—are on the rise.

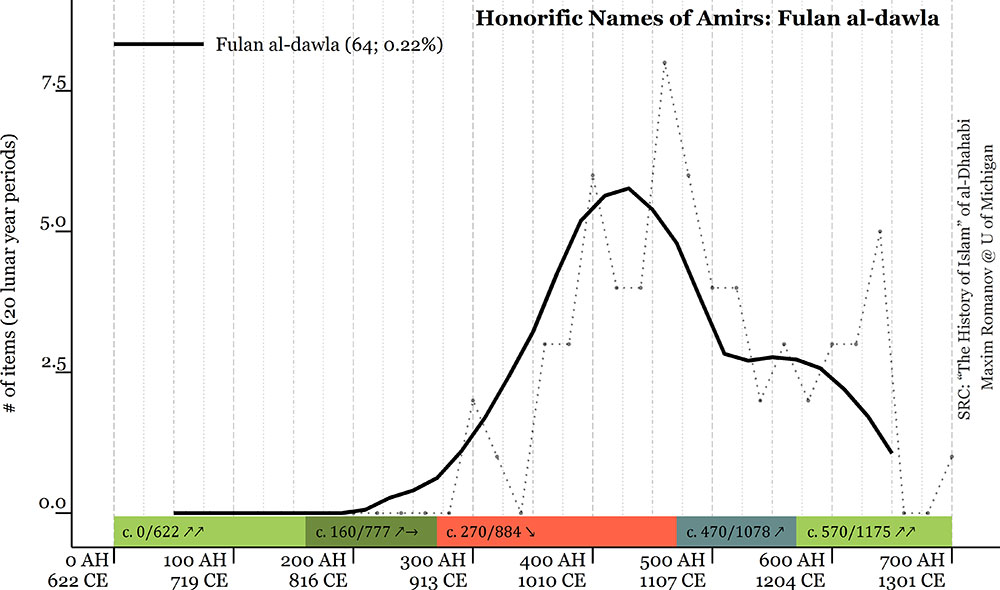

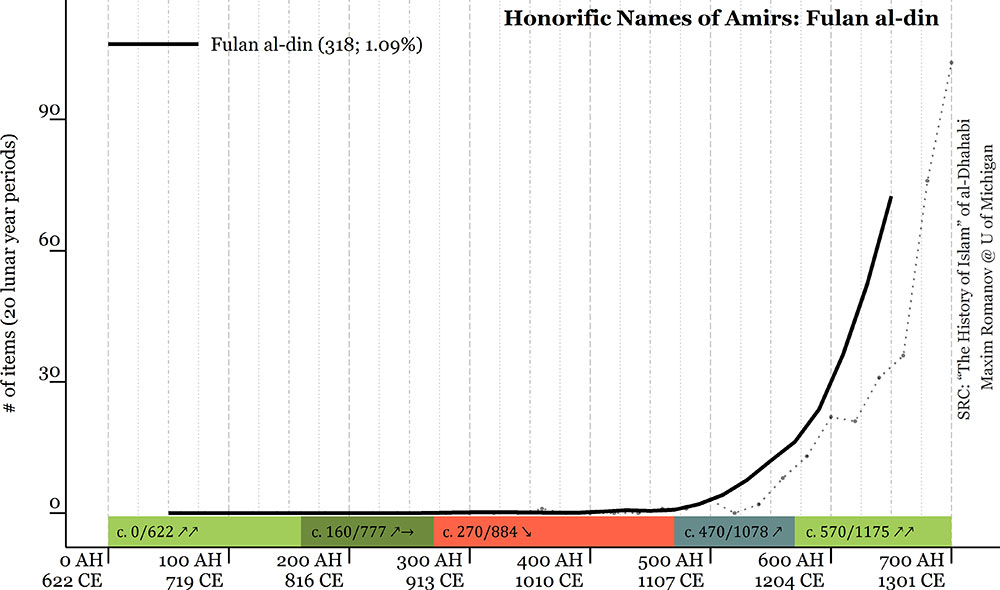

The “Fulān al-dīn” honorifics that in the earlier periods were reserved for religious scholars become very common among the military, while the old pattern of “Fulān al-dawlaŧ” practically disappears (see Figure 15).20 It is not entirely clear whether these names are given to the military by religious scholars or if they are self-claimed (most likely both), but the fact that the military are listed under these honorifics in biographical collections implies that at the very least religious scholars endorsed them.

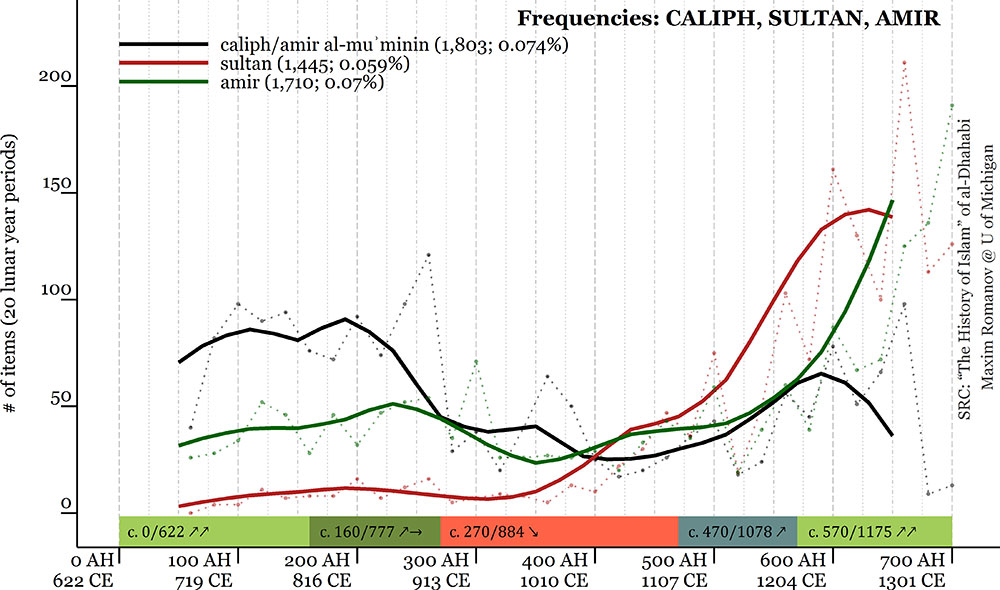

Frequencies of such words as ḫalīfaŧ/amīr al-muʾminīn, sulṭān and amīr in biographies show that the 4th/10th century was a the period (Figure 16) when scholarly attention started shifting from caliphs to sulṭāns and amīrs who were gaining more power and more social presence. This shift in frequencies also neatly marks the end of the period which Hodgson characterized as the High Caliphal Period (in his chronology: c. 692-945 CE),21 and the beginning of the Earlier Middle Islamic Period (in his chronology: c. 945-1258 CE): the era of sulṭāns and amīrs.

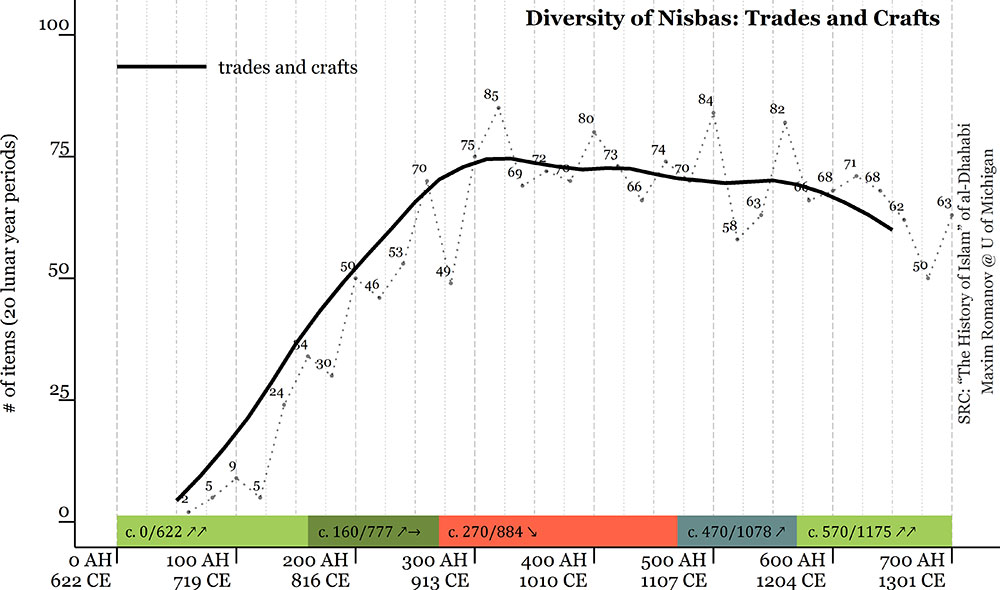

De-civilianization. As was noted above, the share of the civilian sector noticeably decreases after 400/1010 CE. The diversity of crafts and trades within the civilian sector (Figure 17) reaches its highest point around 300/913 CE, when 85 different trades and crafts are represented.22 After 300/913 CE the diversity goes down, getting to the 60s range by the end of the period.

Looking closer into trades and crafts, it can be pointed that several sectors are clearly distinguishable:23 textiles (1, 495), foods (799), metalwork (331), “chemistry” (349),24 clothes (306), finances (278), paper/books (253), brokerage (231), jewelry (218), and sundry services (170).

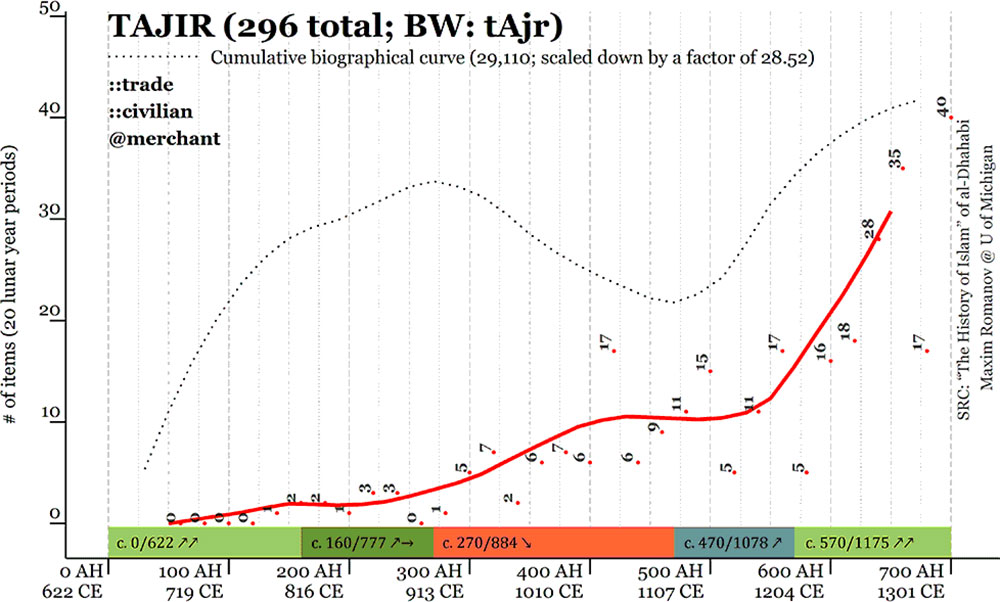

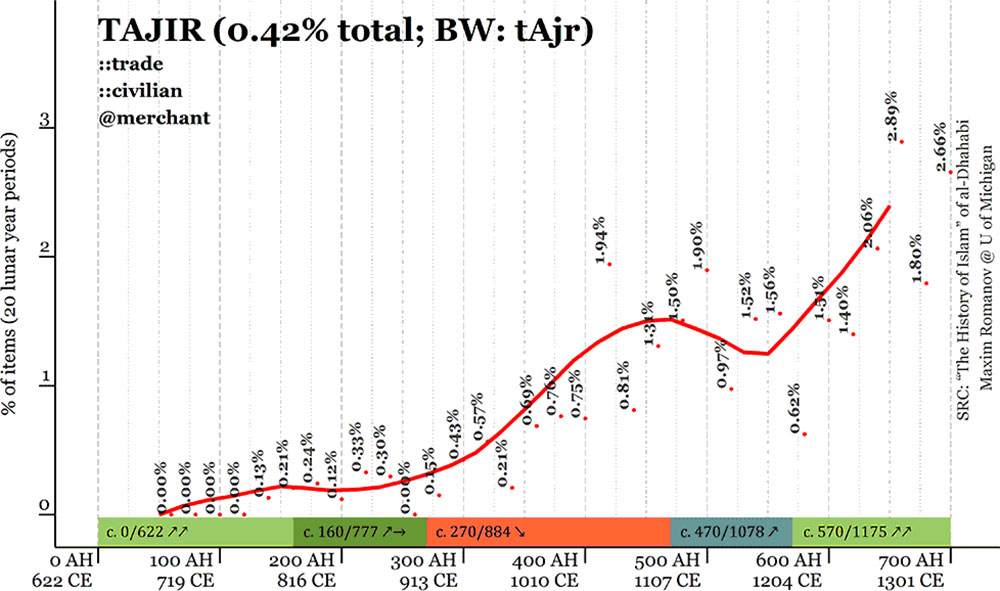

All sectors peak sometime between 300/913 CE and 500/1107 CE, but after that they show steady decline—even in those rare cases when absolute numbers remain quite significant, their percentages unmistakably go down. Practically all individual nisbaŧs show the same trend. Merchants (sing. tājir, 294; Figure 18) constitute the only group that shows a different trend and their numbers actually grow by the end of the period. This is, however, only because this is a blanket category that encompasses all the above listed “industries, ” without emphasizing any specific one in particular. Figure 19 shows the cumulative trend of involvement of religious scholars in crafts and trades. The curve based on absolute numbers (left) shows that numbers of scholars—who were either directly involved in specific crafts and trades or came from families that made their fortune in those areas—remained rather high until 600/1204 CE; relative numbers (right) show that the steady downward trend in this sector begins as early as 440/1049 CE—about three decades before the cumulative biographical curve (470/1078 CE) starts recovering.

By the end of the period the emphasis in identities shifts, and while “secular occupations” are still not uncommon among the learned,25 they are definitely no longer the main focus of biographers, who instead pay more attention to positions and family connections (see section on Professionalization below).

The geographical distribution of these professions is most puzzling. Essentially, all “industries” display the same pattern: the larger the region, the larger the presence of individuals involved in specific “industries.” Iraq always comes first, followed by Iran (representation by sectors varies slightly, but northeastern Iran usually has highest numbers), then Syria and Egypt. Such a geographical distribution of “industries” suggests that occupational nisbaŧs were used as necessary specifiers to distinguish among individuals in large communities.26 This issue might be resolved by adding local biographical collections to the corpus and experimenting with data grouping until some distinctive patterns can be discerned. Data from non-literary sources will be crucial for advancing this inquiry, which requires undivided attention.

Whether this decline of the civilian sector is a result of the actual withdrawal of the learned from trades and crafts, or, the loss of awareness of this part of their identity, the general effect on the development of the religious sector would still be the same: the loss of connections with broader population. It is not that religious scholars stopped maintaining connections with populace at large, but they gradually turned into a self-reproducing class whose members were primarily concerned about their own group interests.

Professionalization & institutionalization of the learned class are another two processes that take place during the period covered in Taʾrīḫ al-islām. These processes have been discussed at length in academic literature,27 although in most cases the emphasis is on institutionalization.28

Here “professionalization” is understood as the growth of complexity of religious learning that leads to its branching into specific disciplines, mastering which eventually requires full-time commitment. Professionalization implies the development of a community of specialists who maintain qualifying standards and ensure demarcation from the non-qualified; ideally, mechanisms of monetary and status compensation for professional services should develop during this process.

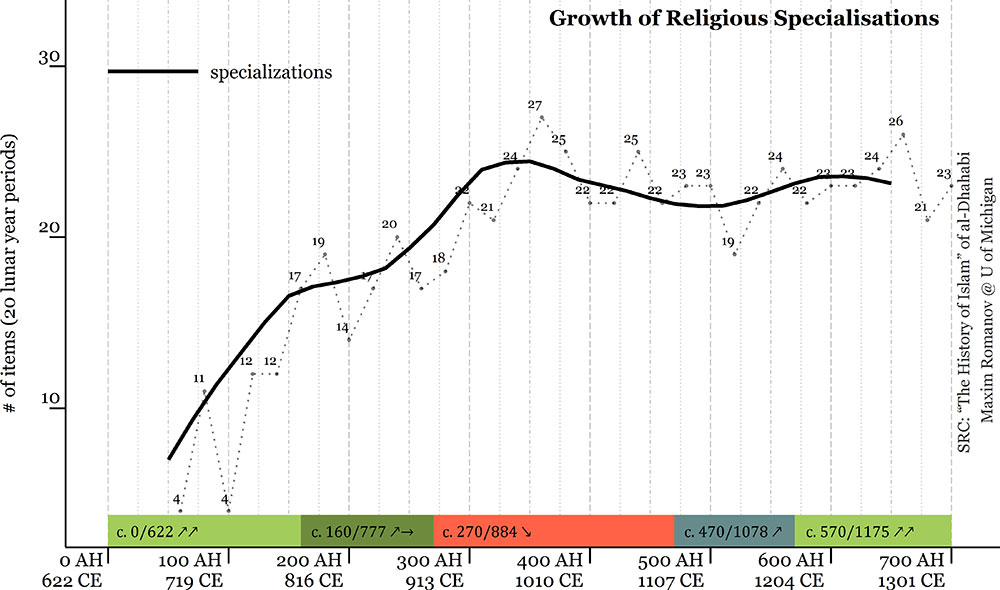

If we agree on recognizing the process of branching of the religious learning into specific disciplines as an indicator of professionalization, we may look at the growth of religious specializations as indicated through “descriptive names.” Figure 20 shows that the process of branching reaches its highest point during 300–350 AH/913–962 CE, after which the number of specializations remains on the same level and fluctuates only slightly.

Although completely devoid of both buzzwords, Melchert’s study is perhaps the most valuable insight into the process of professionalization.29 In his book on the formation of the Sunnī legal schools (maḏhab), Melchert offered three major criteria: the recognition of the chief scholar (raʾīs), commentaries (taʿliqaŧ) on the summaries of legal teachings (muḫtaṣar), as a proof of one’s qualification, and a more or less regulated process of transmission of legal knowledge, through which the achievement of required qualification is ensured. Chronologically, Melchert placed this process for the Shāfiʿīs, Ḥanbalīs and Ḥanafīs in Baġdād of the late 9th—early 10th centuries.30 Keeping in mind this coincidence of Melchert’s close reading of legal ṭabaqāt and my distant reading of Taʾrīḫ al-islām, we may—at least tentatively—consider 300/913 CE to be a turning point in the process of professionalization.

Data from the Taʾrīḫ al-islām shows that professionalization of religious knowledge (around 300/913 CE) is not directly related to scholars’ abandoning their gainful occupations in the civilian sectors, as this process will start only around 430/1039 CE. However, professionalization failed to bring about one very important thing, namely more paid positions for the learned. This must have forced men of learning into difficult position where they had to maintain a delicate, but uncomfortable balance between keeping up with higher standards of religious learning and earning living. The financial difficulties that professionalization imposed on the life of a scholar may have become quite a discouraging factor for the young who were considering career paths. Keeping in mind that the decline of the main curve begins c. 270/884 CE—i.e. roughly around the time when the number of religious specializations reaches its highest point—it is tempting to consider that professionalization has something to do with this decline. After all, a full-time commitment to study religious sciences leaves one no time to earn a living through gainful occupations in the civilian sector. Charging money for teaching religious subjects was considered illicit, and there are hardly any indications that the number of positions for religious specialists grew to compensate for this unfortunate development. To succeed in such conditions, one had to be either extremely resolute or come from a wealthy family to afford the career of a scholar. And since both of these are in limited availability in any society, this could explain the decline in numbers of biographies.

The introduction and spread of waqf institutions is considered a turning point in the institutionalization of the learned. The salaried positions of these institutions offered a solution to the complication of professionalization. Frequencies of references to waqf institutions in biographies (Figure 21) show that they—most importantly the madrasaŧs—become a noteworthy detail of biographies soon after 400/1010 CE, about 100 lunar years after the turning point in professionalization, and a very important one after 500/1107 CE.31

However, by offering salaried positions, the waqf institutions also reconfigured the structure of the learned class, which in the long run had a very negative effect. In his study of medieval Damascus,32 Chamberlain convincingly argued that salaried positions (manāṣib) became one of the major object of contention among the learned who were now concerned about winning and holding as many of these positions as it was possible. One of their strategies was to ensure that the positions stayed within a family—household—which led to the formation of the dynasties of religious scholars and, in the long run, the transformation of the religious class into a rather closed social stratum, to which the word “clergy” became more and more applicable as time went on.

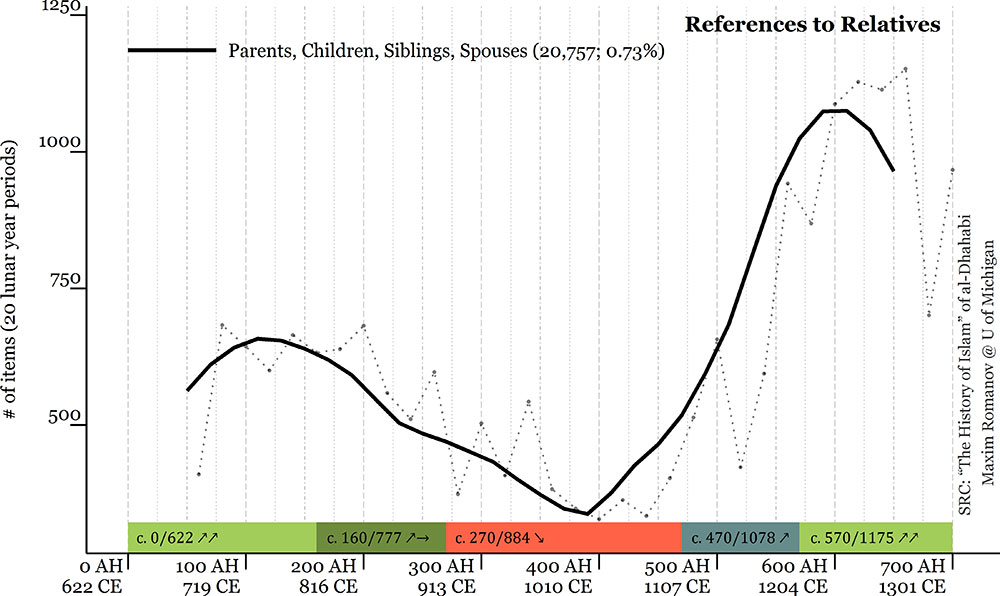

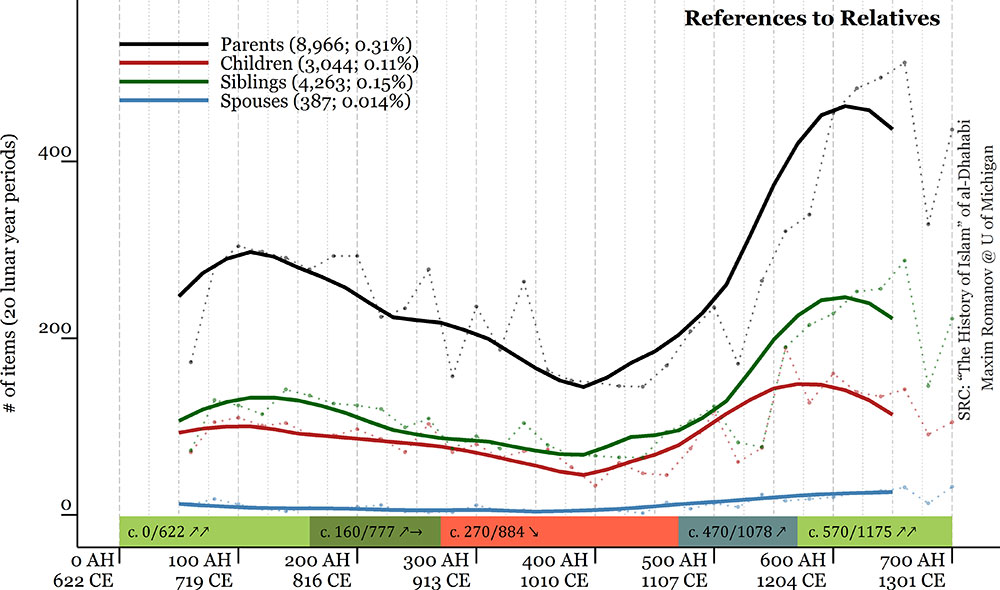

As the data from the Taʾrīḫ al-islām indicate (Figure 22), the role of family connections unmistakably increases after 400/1010 CE. The tribal nature of early Islamic society explains the high frequency of references to close relatives in the early periods. However, references to parents are most frequent—largely to fathers33—which is understandable, considering the importance of lineage through the male line within tribal society. But again, the curve of references goes down steadily between 120/739 CE and 380/991 CE, mirroring the curve of tribal identities that also goes down while the number of biographies keeps on growing. After 380/991 CE references to family members practically skyrocket, and even increase in pace slightly around 500/1107 CE. Unlike in the early period, references to most members of the immediate family become very common: parents (the word “parent, ” wālid[aŧ], become particularly common), siblings (brothers and sisters—aḫū, uḫt), children (sons and daughters—ibnu-hu, bintu-hu, etc.), and, to a lesser extent, spouses (husbands and wives—zawj[aŧ]). The same trend can be seen in the references to uncles, aunts, grandparents and grandchildren. These shifts—not just the growth of frequencies, but also the growth of varieties of familial references—may be interpreted as a shift of scholarly attention from the lineage to the household.

If we accept these rates of frequencies as an indicator of the formation of households, than it appears that scholarly households begin growing earlier than waqf institutions. The growth of scholarly families thus may have been caused by professionalization and then boosted by institutionalization.

Concluding Remark

The presented model is exploratory. It is rather simple, but it is transparent. Explicitly described models can be discussed, compared, modified, and applied to new sources. With models we can stop futile discussions about the meaning and reliability of certain data and start exploring Islamic history experimentally. By developing and testing multiple complex models we can eventually arrive to a better understanding of both our sources and processes that they describe. With models we can compare multiple sources, even evaluate entire genres. Right now, when scholars of Islam are entering the domain of digital humanities, there is a dire need for transparency of our methods—and modeling appears to be the most optimal option—especially if we venture to study the entire digital corpus of classical Arabic sources, which at the moment may have already exceeded 800 million words.

Cited Works

Berkey (1992):

Jonathan P. Berkey. The transmission of knowledge in Medieval Cairo: a social history of Islamic education. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1992.

Bulliet (1979):

Richard W. Bulliet. Conversion to Islam in the medieval period: an essay in quantitative history. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1979.

Chamberlain (1994):

Michael Chamberlain. Knowledge and social practice in medieval Damascus, 1190-1350. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ; New York, 1994.

Cohen (1970):

Hayyim J. Cohen. The economic background and the secular occupations of muslim jurisprudents and traditionists in the classical period of Islam: (until the middle of the eleventh century). Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 13: 16-61, 1970.

Ephrat (2000):

Daphna Ephrat. A learned society in a period of transition: the Sunni ʿUlamaʾ of eleventh century Baghdad. State University of New York Press, Albany, 2000.

Gilbert (1980):

Joan E. Gilbert. Institutionalization of muslim scholarship and professionalization of the ʿUlamāʾ in medieval Damascus. Studia Islamica, (52): 105-134, January 1980. ISSN 0585-5292.

Hodgson (1974):

Marshall G. S. Hodgson. The venture of Islam: conscience and history in a world civilization. Vol. 2. The expansion of Islam in the middle periods, volume 2. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1974.

Humphreys (1989):

R. Stephen Humphreys. Politics and architectural patronage in Ayyubid Damascus. In Clifford Edmund. Bosworth, editor, The Islamic world from classical to modern times: essays in honor of Bernard Lewis, pages 151-174. Darwin Press, Princeton, N.J., 1989.

Humphreys (1994):

R. Stephen Humphreys. Women as patrons of religious architecture in Ayyubid Damascus. Muqarnas, 11: 35-54, January 1994. ISSN 0732-2992.

Jockers (2013):

Matthew L. Jockers. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. University of Illinois Press, 1st edition edition, April 2013.

Makdisi (1981):

George Makdisi. The rise of the colleges: institutions of learning in Islam and the West. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1981.

Melchert (1997):

Christopher Melchert. The formation of the Sunni schools of law, 9th-10th centuries C.E. Brill, Leiden ; New York, 1997.

Moretti (2007):

Franco Moretti. Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History. Verso, 2007.

Moretti (2013):

Franco Moretti. Distant Reading. Verso, 1 edition, June 2013.

Morris (2013):

Ian Morris. The measure of civilization: how social development decides the fate of nations. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2013.

Petry (1981):

Carl F. Petry. The civilian elite of Cairo in the later Middle Ages. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1981.

Romanov (2013):

Maxim G. Romanov. Computational Reading of Arabic Biographical collections with Special reference to Preaching (661-1300 CE). Ph.D., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 2013.

Shatzmiller (1994):

Maya Shatzmiller. Labour in the medieval Islamic world. E.J. Brill, Leiden [The Netherlands], 1994.

Wasserstein (2013):

David J. Wasserstein. Where have all the converts gone? Difficulties in the study of conversion to islam in al-Andalus. Al-Qanṭara, 33 (2): 325-342, February 2013. ISSN 1988-2955, 0211-3589.

Footnotes

- For more details, see Chapter 1 in Romanov (2013). [↩]

- While most humanists remain skeptical in regard to working with big data, the number of studies that show that close reading alone is not enough keeps on growing. They emphasize that case studies based on close reading do not allow for extrapolations; that humanists are prone to putting too much effort into studying objects that are unique and for this reason are least likely to represent larger trends. Most vivid examples can be found in the field of literary history, see, e.g., Moretti (2007), Moretti (2013) and Jockers (2013). [↩]

- See, Moretti (2007), p. 4. [↩]

- For example, Morris (2013) uses the size of the largest urban center as an indicator of the social development of a region to which it belongs. Bulliet (1979) uses onomastic data as the indicator of conversion. [↩]

- For valuable examples of modeling “big data, ” see: Moretti (2007), Morris (2013); also see http://orbis.stanford.edu/ for the geographical model of the Roman world, developed by Walter Scheidel and Elijah Meeks. In the field of Islamic studies: Bulliet (1979). [↩]

- Bulliet’s model of conversion is a great example of this. The very fact that this study is still criticized after more than three decades from its publication shows that a solid model cannot be discarded through a critique of where it fails, if otherwise it still remains plausible and coherent. For the most recent critique, see: Wasserstein (2013). [↩]

- Both toponyms proper and toponymic nisbaŧs linked with relevant toponyms. Toponymic data is crucial for our understanding of the social geography of the classical Islamic world. For my modeling of the geography of the Islamic world based on the data from Taʾrīḫ al-islām see, Romanov (2013), p. 35-37, 41-42, 87-113. [↩]

- Romanov (2013), p. 28-51. [↩]

- For a detailed discussion, see Romanov (2013), p. 43-46. [↩]

- See, Cohen (1970). [↩]

- Petry (1981). For the “Glossary, ” see pp. 390-402. [↩]

- Shatzmiller (1994); For extensive lists of names/occupations, see pp. 101-168, 410-424. [↩]

- Some wazīrs rivaled their “employers” in influence. The most prominent examples are the Barmakid family that served the ʿAbbāsid caliphs and Niẓām al-mulk who served Mālikšāh, the Great Saljuq sulṭān. [↩]

- There are 322 physicians in the ʿUyūn al-anbāʾ fī ṭabaqāt al-aṭibbāʾ of Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿaŧ (d. 668/1270 CE) and quite a few physicians are Jews and Christians, judging by their names. al-Ḏahabī’s count of physicians is about 200 which can be considered a very thorough coverage, since Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿaŧ’s book is devoted exclusively to the physicians (and as it often happens, tends too overstretch the definition of the group), while al-Ḏahabī’s book is a general history. [↩]

- The first major peak of the nisbaŧ al-Maḫzūmī is around 150/768 CE and geographically it peaks largely in the Central Arabian Cluster (65 al-Maḫzūmīs). [↩]

- Hodgson (1974), p. 64. [↩]

- Unfortunately, at the moment my algorithms are not tuned well enough to trace all individuals who belonged to the military sector. The nisbaŧ al-amīr should serve well as an indicator: it is the most frequent “descriptive name” within the military sector and it is the easiest to trace computationally. [↩]

- Most prominently, women from their households, see, Humphreys (1994). [↩]

- See, for example: TI, 28, 311-312; TI, 29, 68-76; TI, 37, 57-58; TI, 37, 185-186; TI, 38, 157-158; TI, 39, 370-387; TI, 41, 161-164; TI, 42, 407; TI, 44, 220; TI, 45, 119; TI, 45, 164; TI, 45, 311-313; TI, 45, 359; TI, 45, 402-406; TI, 46, 87-88; TI, 46, 289; TI, 46, 431-432; TI, 47, 165; TI, 47, 308; TI, 49, 192; TI, 50, 264; TI, 51, 196-197; TI, 51, 369-370; TI, 52, 368; TI, 52, 409-411. On the military patronage, see also: Humphreys (1989). [↩]

- Somehow, the “Fulān al-dīn” names still have a strong steel aftertaste. The most common first components of the “Fulān al-dawlaŧ” pattern are Sayf al-dawlaŧ, “Sword of the Dynasty;” Nāṣir..., “Helper...;” Naṣr, “Victory;” Muʿizz, “Strengthener;” ʿIzz, “Strength;” ʿAḍud, “Support;” Tāj, “Crown;” Bahāʾ, “Splendor;” Ḥusām, “Cutting Edge.” The most first components of the “Fulān al-dīn” pattern are: Sayf al-dīn, “Sword of Religion;” ʿIzz..., “Strength...;” Jamāl, “Beauty;” Badr, “Full Moon;” Shams, “Sun;” Ṣalāḥ, “Goodness;” Ḥusām, “Cutting Edge;” Quṭb, “Pole;” ʿAlam, “Banner.” [↩]

- There is also a late peak that corresponds to the restoration of the independence of the ʿAbbāsid caliphate during the second half of the 6th/12th century, but it is short-lived. [↩]

- I should remind the reader that only nisbaŧs that are used to describe at least 10 individuals are considered in this analysis. [↩]

- Largely following Shatzmiller’s classification, see: Shatzmiller (1994); these sectors often overlap. [↩]

- Trades that involve dealing with any complex compounds: al-ʿAṭṭār, “druggist, perfumer;” al-Ṣaydalānī, “apothecary, druggist;” al-Ṣābūnī, “soap maker/seller” etc. [↩]

- The decline does not appear as staggering as, for example, Cohen’s (Cohen (1970)) study argued. [↩]

- Very similar to what Bulliet argued regarding toponymic nisbaŧs: “For example Karkh, a popular quarter of Baghdad, appears in the nisba al-Karkhī when representation from Iraq is high. When the proportion is smaller, the name of the major city itself is a common nisba. In the example given, a later resident of Karkh would appear as al-Baghdadī. Finally, when the proportion is very low, the nisba will frequently be derived from the entire province, that is, al-Baghdadī becomes al-ʿIrāqī.” (Bulliet (1979), p. 12). [↩]

- The most important studies are: Makdisi (1981), Berkey (1992), Chamberlain (1994). To a large extent Berkey’s and Chamberlain’s studies are responses to Makdisi’s “over-institutionalization.” [↩]

- It seems that Gilbert is the only one to use this term in her study of the learned of Medieval Damascus: see, Gilbert (1980). However, in her study this term appears to blend into institutionalization and both become practically indistinguishable. Other scholars mention professionalization almost exclusively with the reference to Gilbert’s work. See, for example: Chamberlain (1994), p. 70; Ephrat (2000), p. 104, 179. [↩]

- Melchert (1997). [↩]

- The failure of the Mālikīs Melchert explains by their being too closely linked to the caliphal patronage and when the caliphs were eclipsed, so were the Mālikīs. See: Melchert (1997), p. 176. [↩]

- The decline of the frequency of the word madrasa should not be interpreted as a decline of this institution, but rather as a change in the form of reference in general: most madrasaŧs are referred to by their “al-Fulānīyaŧ” names (see Figure 14). [↩]

- Chamberlain (1994). [↩]

- The most common references are the forms of abū, “father.” Since this word is also the essential part of kunyaŧ, an extremely common patronymic element of the Arab/Muslim name, only its forms with pronominal suffixes—such as abū-hu, “his father”—are considered. The same principle is applied to other ambiguous family terms. [↩]