The main goal of OpenITI mARkdown is to provide a simple system for tagging structural, morphological and semantic elements in premodern and early modern Islamicate texts of the OpenITI corpus. The use of OpenITI mARkdown will allow one to engage in the computational analysis of texts in the same way as allowed by the more complex and time-consuming tagging schemes such as TEI XML; OpenITI mARkdown will also facilitate the conversion of the large volume of Islamicate texts into TEI XML, which is now the standard format for digital editions. In principle, OpenITI mARkdown does not require any special editor, but the current implementation relies on EditPad Pro, which supports right-to-left languages, Unicode, and large files. However, it is the support of custom highlighting and navigation schemes that makes this text editor particularly convenient for OpenITI mARkdown.

OpenITI mARkdown is not meant to be a comprehensive standard, but rather a light-weight tagging scheme that renders texts machine readable and can be adapted to specific research tasks. The scheme consists of a set of unified patterns, but also includes custom patterns that facilitate analysis of specific types of data. These patterns can be divided into structural (unified), morphological (unified, customizable) and semantic (unified customizable, but also custom). The scheme currently accommodates a variety of research inquiries.

Brief Description

- Texts in OpenITI are automatically converted into OpenITI mARkdown, and in most cases, only structural tagging is required—in other words, tagging headers of chapters, sections, subsections and and other logical units.

- Download and install EditPad Pro. EditPad Pro works on Windows only; if you are using Mac or Linux, you can still use it with some virtualization option; the combination of Parallels, Windows 10 and EditPad Pro works well on Macs (The size of the virtual machine with Windows 10 is only about 10-15Gb).

- Download OpenITI mARkdown schemes from GitHub (https://github.com/OpenITI/mARkdown_scheme), and unzip, and copy all the files into

%APPDATA%\JGsoft\EditPad Pro 7(Note: make sure that EditPad Pro in not running: you need to doFile > Exitto completely close it). - The scheme is automatically activated in EditPad Pro by the first line in the file, which must be:

#####OpenITI#(called magic value in EditPad Pro). - Texts in the repositories of the OpenITI Project have already been preprocessed and basic structural tags should already be implemented. Opening any of these texts in EditPad Pro should automatically activate OpenITI mARkdown scheme. NB: Since the corpus is work in progress and many texts have not yet been manually edited, tags that may appear in texts do not necessarily correspond to proper OpenITI mARkdown tags!

- The tagging of structural elements of the text boils down to collating the electronic text with the paper edition it is based on, and tagging the main logical units in the electronic text:

- the headers of chapters (

### |), sections (### ||), subsections (### |||), etc. The entire text of a header must be on the same line (the entire text of the header will be highlighted, if everything is correct). - and information units: biographies (

### $), descriptions of events (### @), and dictionary entries (also### $) - If a logical unit is tagged correctly, the color of a tagged unit’s header will change accordingly.

- the headers of chapters (

NB: Tagging must be done through the collation of the electronic text of a book with the printed edition on which the electronic text is based. Most editions can be easily found online as PDF files (‘googling’ the title—in the original language—usually brings up a lot of results; PDFs are most likely to be on Archive.org)

Detailed Description

File structure

NB: On the general organization of OpenITI, see the relevant section.

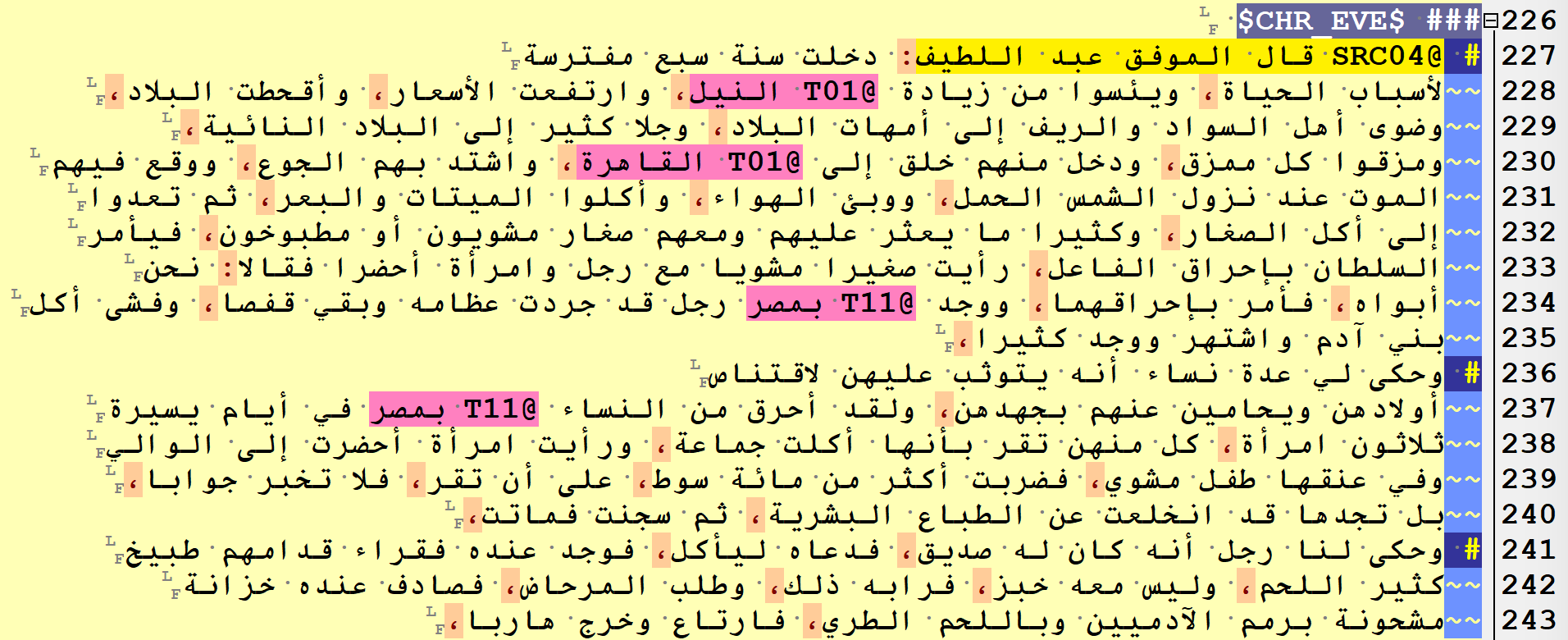

An OpenITI mARkdown file includes three main sections, which are shown on the screenshot above. They are 1) magic value; 2) non-machine readable metadata header; 3) text of the book proper.

Magic value

Magic value is the first line of text in the file that that activates the OpenITI mARkdown scheme in EditPad Pro. This value is ######OpenITI# (nothing else should be on the first line of the file, otherwise the scheme will not be activated).

Non-machine-readable metadata header

This data presents the description of a text salvaged from the original collections. These are the lines that start with #META# .... Since most of metadata in existing collections suffers from a variety of inconsistencies, these lines are not machine readable, yet they often contain all necessary information for a bibliographical reference. Machine-readable metadata will be gradually collected into corresponding *.yml files; see below for more details);

Text of the book

After these two elements, the text of an edition begins. The first two elements are separated from the text of an edition with the line that contains the following: #META#Header#End# (Again, this is the only element that must be on the line).

The screenshot below shows all thee main elements at the top of a OpenITI mARkdown file.

Text structure

Tagging patterns in a text fall into two main groups: 1) structural patterns, which include basic structural patterns & logical unit patterns; and 2) analytical patterns, which include morphological patterns, semantic patterns & a small numbers of custom analytical patterns.

The main difference between these two groups can be described as follows. Elements of the first group can be found in printed versions of texts, and thus, the tagging of these elements can be performed by anyone who has basic familiarity with Arabic script and has an ability to collate digital text with its printed original. Elements of the second group can be inserted in a text only by those who are well acquainted with that specific text, and thus, tagging with analytical patterns is to be performed by scholars for specific research purposes. In terms of the workflow, tagging of structural patterns must precede tagging with analytical patterns.

Structural Patterns

Basic structural elements

Basic structural elements include the following. Basic structural elements have been automatically implemented in all the texts of the OpenITI, although, because of the inconsistencies in initial formatting of these texts some issues remain. Basic structural elements include 1) paragraphs; 2) page numbers (whenever applicable); 3) verses of poetry, and 4) milestones.

— Paragraphs and lines

In premodern Arabic texts paragraphs as units are not particularly reliable. Yet, if a certain electronic text reproduces a printed edition, it is worth preserving its division into paragraphs. Each paragraph begins with a hashtag, #.

While EditPad Pro handles large files very well, it has problems with long paragraphs (or, more correctly, lines). For this reason, long paragraphs are split into shorter lines, where each line starts with ~~ (two tildas).

— Page numbers

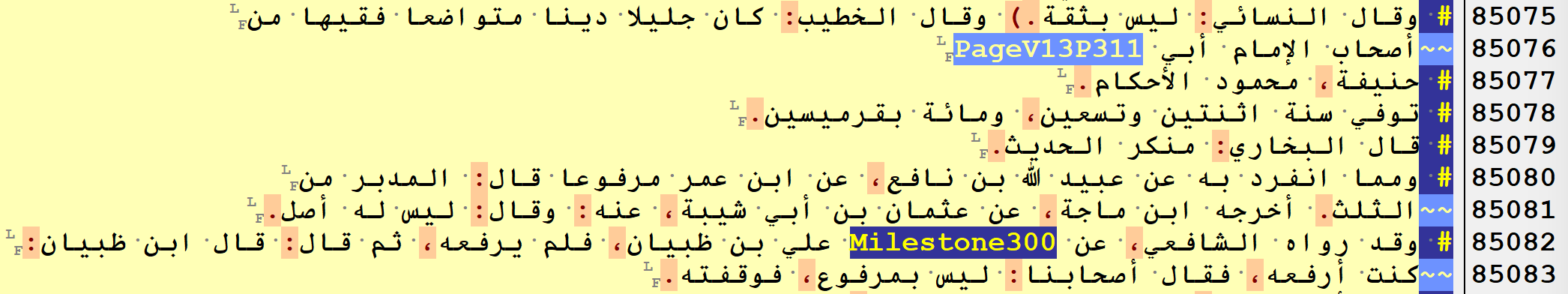

Most of electronic texts preserve pagination. OpenITI mARkdown supports the following format PageV##P###, where V## is the volume number, and P### is the page number. Volume number must be two digits, page number—three (padded with zeros when necessary). Thus, PageV05P022 stands for Vol. 5, p.22. Page number tags are inserted at the end of the corresponding page. In some texts this is not properly implemented yet. For an illustration, see “Milestones” section below.

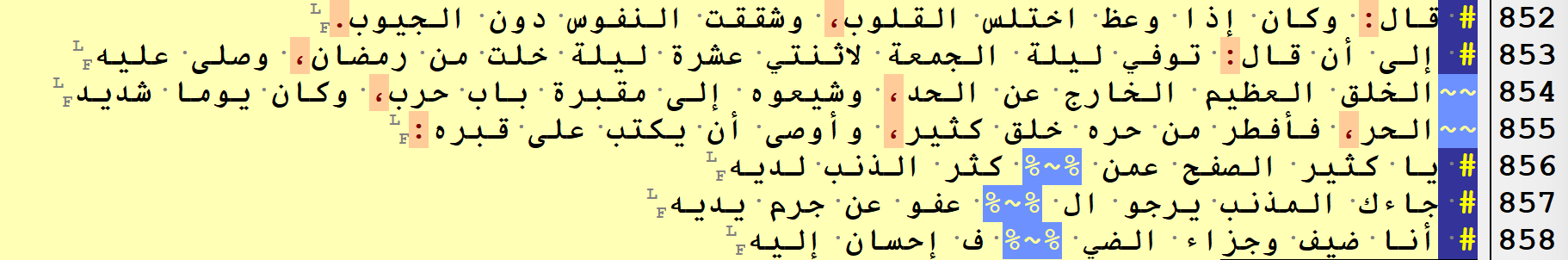

— Verses of poetry

Each verse must be on its own line (beginning with a paragraph tag # ), and hemistichs divided with %~% (when not applicable this tag can be places either at the beginning of the end of a line). Verses are not tagged consistently through out all the texts, since the tagging of verses was not consistently implemented in the initial versions of texts.

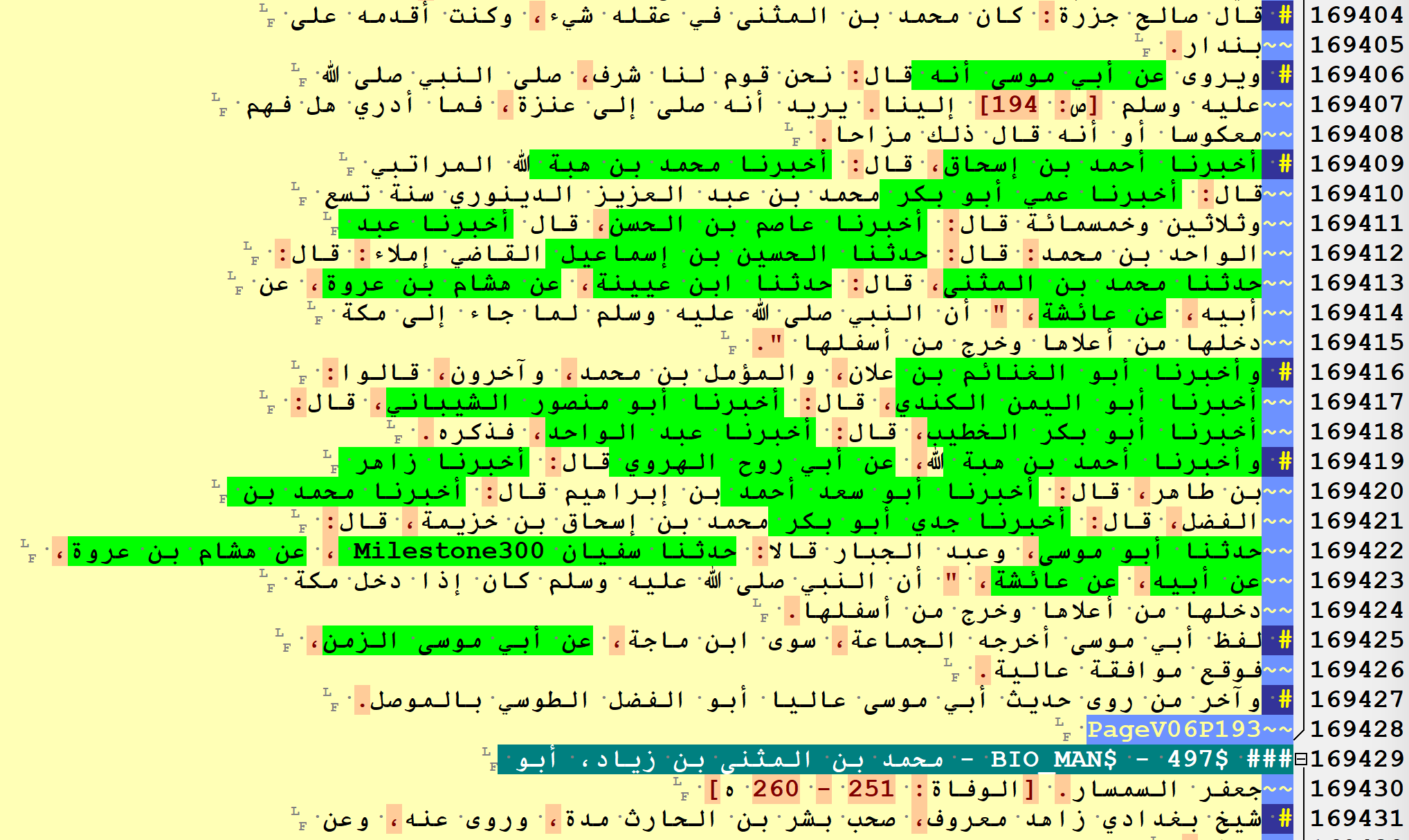

— Milestones

Milestones (Milestone300) are automatically inserted tags that split texts into 300-word units. Having an ability to split text into equal chunks is helpful for a variety of analytical approaches. These tags should not be moved or removed.

Logical unit patterns

Logical units are the main units into which a specific text is divided, i.e. chapters, sections, lexical entries, biographies etc.

— Section headers

All major sections of a text usually have headers. Headers of sections are tagged in the following manner: 1) ### — three hashtags at the very beginning of the line; 2) which are followed by the pipe symbols—| —whose number corresponds to the level of a header; 3) the pipes are then followed by the text of the header, which must be on this line entirely (i.e., followed by \n, “new line” character). If there is no text header, the line may remain empty (after the pipes).

### | First Level Header (red)

### || Second Level Header (orange)

### ||| Third Level Header (yellow)

### |||| Fourth Level Header (green)

### ||||| Fifth Level Header (blue)

The animated image below demonstrates the tagging of headers. Each level has its own color (following the rainbow colors), if tagged correctly.

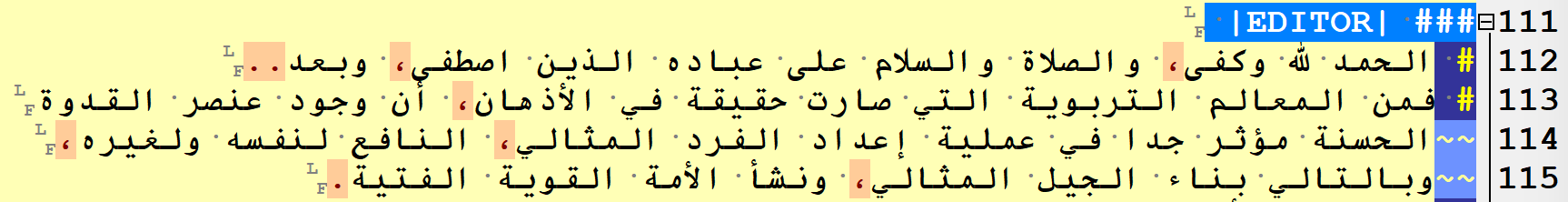

—> Editorial sections

Editorial sections are tagged with ### |EDITOR|, which also must be on a separate line.

Main information units

For sources that are made of serial units of information—for example, biographies in biographical collections; lexical, onomastic and toponymic entries in dictionaries; descriptions of events in chronicles and the like—there is a series of tagging patterns which classify those units of information. Current patterns do not cover all relevant cases and will be added on as-needed basis.

Using OpenArabic mARkdown, one needs only to mark the beginning of each information unit. Each unit can be marked with either a simplified or full tag. Simplified tags are short, which makes them ideal for manual tagging. Simplified tags are, however, ambiguous. Full tags are more readable and source independent. Full tags are particularly important when information from multiple sources are processed at the same time.

— Dictionary units

Arabic dictionaries usually include information units of the same types, so one simplified tag—### $ [a dictionary item]—is sufficient. The full tags depend on the nature of each dictionary and at the moment include “descriptive names” (nisbaŧs), toponyms, lexical items, and book titles. Tags for them are as follows:

### $DIC_NIS$ [a descriptive name entry]

### $DIC_TOP$ [a toponym entry]

### $DIC_LEX$ [a lexical entry]

### $DIC_BIB$ [a book title]

— Biographies and Events

RE: _multiple_

Biographical collections often include several types of information units. Moreover, there are plenty of sources that combine features of both biographical collections and chronicles (“obituary chronicles”), so one often has to deal with a variety of information units in the same text. For this reason, the main simplified tags are as follows:

### $ [a biography of a man]

### $$ [a biography of a woman]

### $$$ [a cross-reference and/or repetition, for both men and women]

### $$$$ [a list of names]

### @ [a historical event]

### @ RAW [a batch of historical events]

NB: ### @ RAW can be used to tag blocks of historical events when it is not immediately clear when one information unit ends and another begins. With these tags in place, one can return to an unfinished batch later, read it more carefully, and split properly into single units. There is also, of course, a conceptual and methodological issue with regard to what constitutes an ‘event’. For the purposes of algorithmic analysis, [the “description of an] event” is a structurally and thematically complete unit of text that describes an entity that has 5 properties: subject, predicate, object, time and place. In other words, it is something that can be grouped into categories, graphed across time, and mapped in space.

Full tags are as follows:

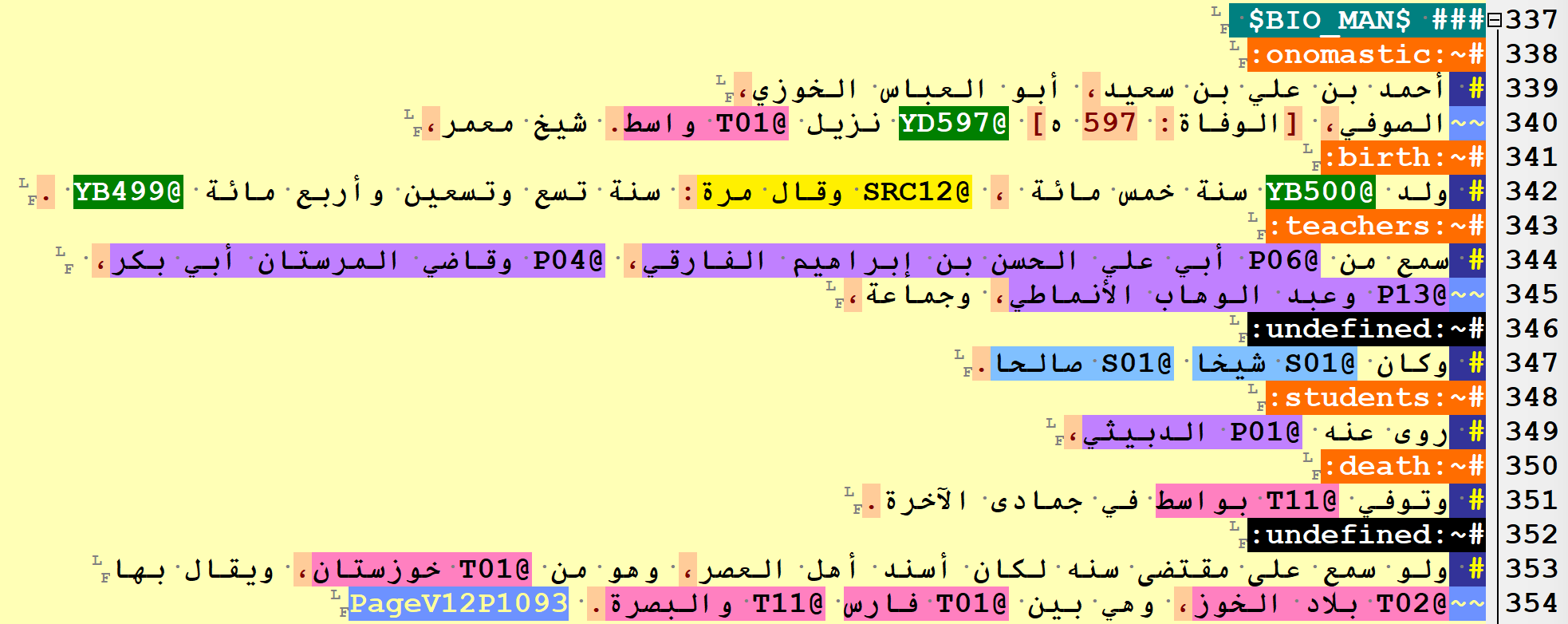

### $BIO_MAN$ [a biography of a man]

### $BIO_WOM$ [a biography of a woman]

### $BIO_REF$ [a cross-reference, for both men and women]

### $BIO_NLI$ [a list of names]

### $CHR_EVE$ [a historical event]

### $CHR_RAW$ [a batch of historical events]

— Doxographical items

NB: David Bennet; added: September 23, 2016

The following tags are section tags to be places at the beginning of a relevant section: (1) ### $DOX_POS$ for sections dealing with doxographical/theological positions; (2) ### $DOX_SEC$ for descriptions of religious groups (“sects”). These can be used doxographical texts where information is presented in a serial fashion (i.e., the entire text is made of doxographical units of these kinds); in texts that address doxographical issues on top of other things, morphological pattern should be used.

Analytical patterns

Analytical patterns are meant to provide scaffolding for tagging complex entities in such a way that would allow for complex automatic manipulation of tagged data for the purposes of computational analysis. The analytical patterns are meant to be adjustable for specific research questions and include semantic and morphological patterns. Semantic patterns are used to tag specific types of named entities (e.g., toponyms, individuals, date statements, sources, etc.), semantic contexts (see, Open Tagging Pattern), and morphological units, or thematic text passages.

Semantic Patterns

— Named Entities

These tags are used to provide relevant metadata to specific words and phrases. In other words, you use these to identify certain words or phrases as references to toponyms, individuals, date statements, sources, and social/onomastic descriptors. The list of taggable named entities will be expanded.

All tags have similar structure @ + CODE + two numbers. CODEs have two variations: 1) long (three letters) and 2) short (one letter). Triliteral CODEs are used for automatic tagging with scripts and entity lists; one-letter short CODEs are used for manual tagging and disambiguation of automatic tags.

XX, two numbers, indicate:

- the length of an attached prefix. For example, if

wa-orbi-are attached to an entity, the first number must be1, which means that 1 character from the beginning must be removed) - the length of the entity. If the entity is a bigram (Madīnaŧ al-Salām), number

2must be used (both words will be automatically highlighted).

NB: The tags have two varieties: a long one and a short one. The long one will be used for automatic tagging (the automatic tagger is in progress), while the short one will be reserved for manual tagging, as shorter tags are easier to type in manually; additionally, the conversion of an automatic tag into a manual one in the process of edition and disambiguating is more efficient by deleting two characters, rather than adding them.

—> Biographical characteristics

- Automatic long tag:

@SOCXX - Manual short tag:

@SXX

—> Years AH

Years AH can be tagged in the following manner (where # is a digit; there must be spaces on both sides of the year tag):

YB####— a year of birth, as mentioned in a biography; for example,@YB510means that a biographee was born in the year 510 of the Islamic hijrī calendar.YD####—a year of death, as mentioned in a biography; for example,@YD597means that a biographee died in the year 597 of the Islamic hijrī calendar.YY####—any other type of year references mentioned in a text.YA####— age in years.

—> Toponyms

- Automatic long tag:

@TOPXX - Manual short tag:

@TXX

—> Individuals (Persons)

- Automatic long tag:

@PERXX - Manual short tag:

@PXX

—> ‘Sources’

This pattern is to tag ‘sources’ of information (for statements such as qāla fulān b. fulān). These are tagged in the following manner:

- Automatic long tag: no pattern

- Manual short tag:

@SRCXX

— Open Tagging Pattern

[NB: accidentally, the highlighting is dropped from the current scheme; it will be added in the next version.] This pattern is easily adjustable for tagging specific semantic contexts. Unlike the named entities tags above, these serve only as pointers to a relevant context, and are not meant to be connected to specific vocabulary in a text.

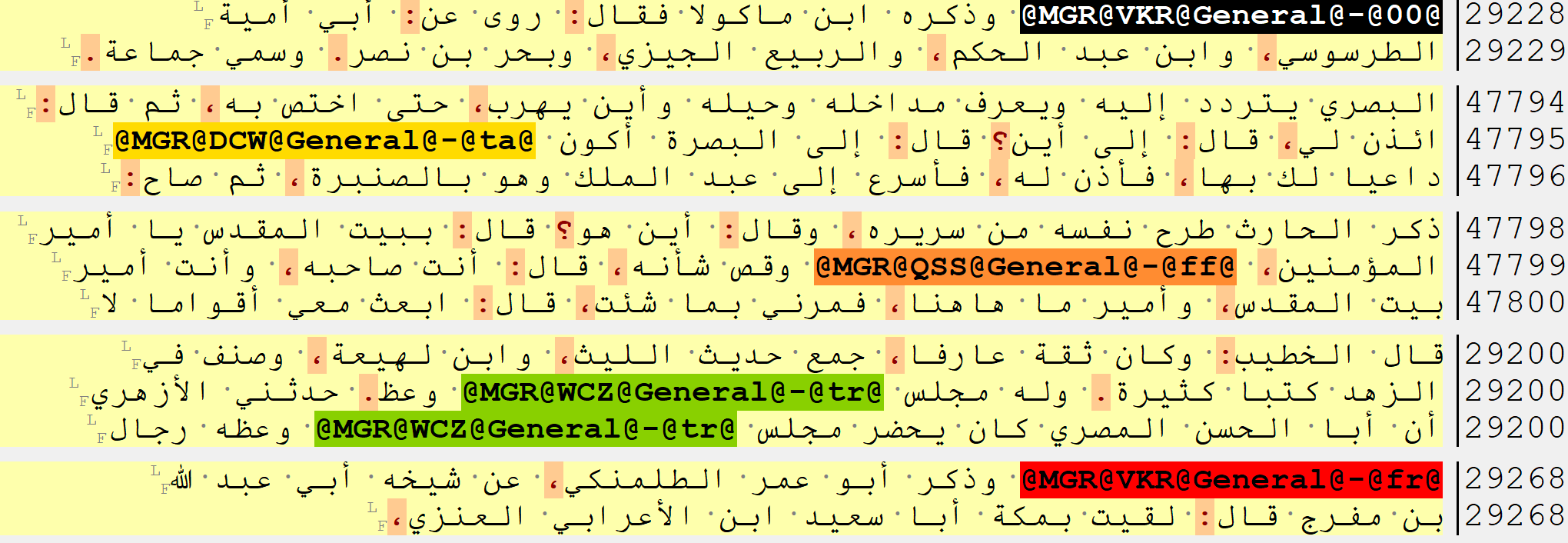

The overall pattern is @USER@CAT_SUBCAT_SUBSUBCAT@, where USER is an alias of a researcher introducing a pattern (three-letter initials is an option—MGR in my case); CAT_SUBCAT... represents categorical branching, where categories are defined by a researcher for specific purposes.

MGR

├── WACZ

│ ├── education

│ │ ├── quran

│ │ ├── hadith

│ │ └── fiqh

│ └── sermons

│ ├── hell

│ ├── paradise

│ └── love

├── KHUTBA

│ ├── education

│ │ ├── punishment

│ │ ├── hadith

│ │ └── fiqh

│ └── sermons

│ ├── hell

│ ├── paradise

│ └── love

└ etc.

Above is a snapshot of a scheme that I used for tagging biographies of preachers. In this example, I am looking into individuals involved into two different forms of preaching—waʿẓ and ḫuṭbaŧ, their education backgrounds and topics of their sermons. Thus, my tag in the case of a wāʿiẓ who had training in fiqh will look as follows: @MGR@WACZ_education_fiqh@. In combination with chronological, geographical and social information (derived from nisbaŧs), one can get a perspective on how many individuals involved in waʿẓ had training in fiqh and if there are any chronological, geographical and social peculiarities to this information.

It is vital to keep track of tags one introduces and avoid creating too many of them. Another useful strategy is to keep them short, for instance: @MGR@WCZ_ed_fqh@ (it is your own decision, of course, how to balance brevity and readability).

Open Tagging Pattern – for automatic tagging (testing in progress)

These tags are conceptually similar to the ones described in the previous section, but used in automatic tagging of texts using relevant gazetteers of terms and keywords.

The tag pattern is slightly different (highlighted with different colors, depending on the last element of the tag): @[A-Z]{3}@[A-Z]{3,}@[A-Za-z]@-@[0tf][ftalmr]@, where:

@[A-Z]{3}(three capital letters — only letters from the ASCI range) is for scholar’s initials or the abbreviation of the name of a project.@[A-Z]{3,}(at least three capital characters — only letters from the ASCII range) is for the class of a tagged item (for exapmle,PERSON,TOPONYM,EVENT, etc.)@[A-Za-z]+@(any number of letters — from the ASCII range only) is for the category of a tagged item (for example, the category would be @ProphetMuhammad@ for such tagged items as rasūl Allãh, Muḥammad ṢLʿM, al-nabī ṢLʿM, etc.)-@[0tf][ftalmr]@(two small letter characters from the list) is for the review status of tagged items; for example, the first character implies:0— review required;t— most likely true;f— most likely false; the second character implies:0— review required;t— true;m— manually classified item;a— automatically classified item;l— logically classified item;r— reviewed item;- the review status element determines the color of the entire tag to facilitate tag review; the following combinations can be used:

-@00@— element means that review is required; this is automatically inserted tag; this element highlights the entire tag in black.-@tr@and-@fr@— the element means that the item has been reviewed (r) and a given item has been confirmed to be either true (t) or false (f). The-@tr@element highlights the entire tag in light blue; the-@fr@element — in red.-@tt@,-@ta@,-@tm@,-@tl@— most likely true matches that still require review; these are automatically inserted tags (only if a KWIC data list is used). These elements highlight the tag in yellow.-@ff@,-@fa@,-@fm@,-@fl@— most likely false matches that still require review; these are automatically inserted tags (only if a KWIC data list is used). These elements highlight the tag in orange.

- the review status element determines the color of the entire tag to facilitate tag review; the following combinations can be used:

Simplification: work in progress

- The classifier tail (e.g.,

-@tt@) is not really necessary when a result is disambiguated astrue positive, so in fact it can be completely removed, making structure simpler. -@tt@is tricky to remove, because of non-letter characters and the mess that they create; Solution: remove non-letter characters from the tail, simply stacking it to the tag like@MGR@WCZ@Sermon@true.- Structure of the open tagging pattern for semantic annotation: it is beneficial to use a triple-like structure, i.e., SUBJECT-PREDICATE-OBJECT, since one can describe/code anything with this structure and it can be parsed into any other data format. One has to keep track of the tags, of course, but a simple frequency analysis can help to clean them up later.

Morphological Patterns

Morphological patterns are designed to tag passages of text that can be categorized thematically. The tag is inserted on a separate line before the beginning of a passage. There is no closing tag proper; the tag for the next thematic passage serves as a closing tag for the previous passage. The pattern is as follows:

#~:category:, wherecategoryis defined by a scholar for relevant research questions.#~:undefined:can be used to tag the beginning of a passage without assigning a category.- While starting to work with a new text, it makes sense to use only

#~:undefined:, until categories start to flesh out from tagged examples. #~:undefined:can also be used as a pseudo closing tag, when only specific morphological elements need to be tagged (Let’s say, you are interested in tagging only letters in a vast text: you add#~:letter:in the beginning of the relevant passage, and#~:undefined:—at the end; both go on separate lines between morphological passages).

- While starting to work with a new text, it makes sense to use only

The tag can be followed by semantic keywords, following the format of the Open Tagging Pattern (see above).

Custom Analytical Patterns

These patterns are designed to tag very specific structures in texts and for the moment there are only two main patterns that are used in particular research projects. The point of these tagging patterns is to provide just the bare minimum of structure into a natural text so that is could be parsed with a script and converted into machine-readable data.

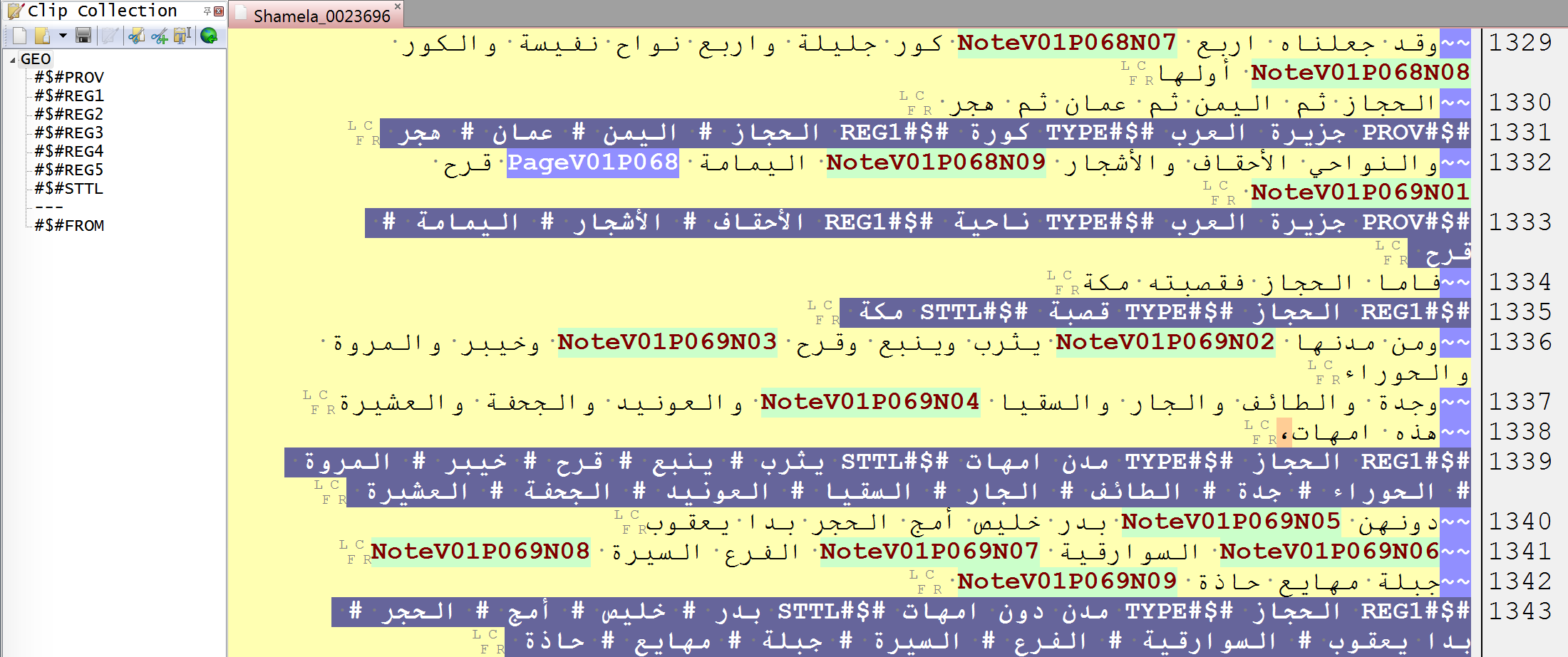

— Geographical units

Geographical texts—such as comprehensive geographies—contain a lot of data that can be used for modeling historical processes in space. Of particular importance are administrative divisions and trade routes, which often come with distances. Data tagged with these patterns can be computationally manipulated. For example, see geographical divisions from al-Muqaddasī’s Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī maʿrifaŧ al-aqālīm visualized in a sunburst graph, or this comparison of al-Muqaddasī’s data with that of Cornu (Credits: Masoumeh Seydi, Leipzig University).

—> Administrative Divisions

RE: #\$#(PROV|REG\d)# .*? #\$#TYPE .*? #\$#(REG\d|STTL) ([\w# ]+) $

Most descriptions fit into the following scheme WORLD: PROVINCE > TYPE > (REGION) > TYPE > SETTLEMENT. In the actual text, relevant information is tagged essentially as ‘triples’ of SUBJECT > PREDICATE > OBJECT (with multiple OBJECTs that will be parsed out at a later stage):

#$#PROV toponym #$#TYPE type_of_region #$#REG1 (toponym #)+

#$#REGX toponym #$#TYPE type_of_region #$#REGX (toponym #)+

#$#REGX toponym #$#TYPE type_of_settlement #$#STTL (toponym #)+

Note: Clip collection can be used to insert relevant patterns into the text.

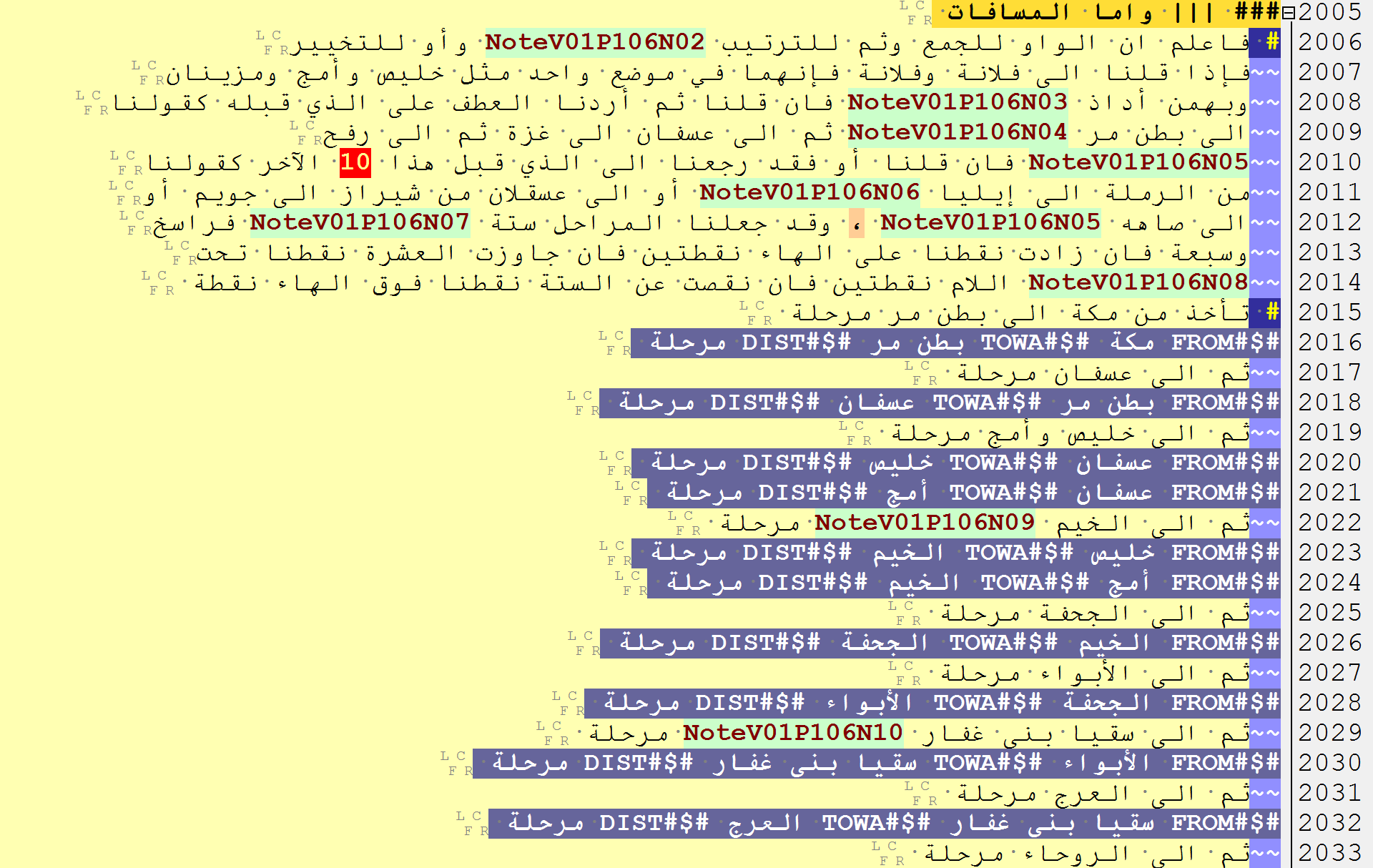

—> Routes and distances

RE: #$#FROM .*? #$#TOWA .*? #$#DIST .*

Route sections with distances are tagged in the following manner:

#$#FROM toponym #$#TOWA toponym #$#DIST distance_as_recorded

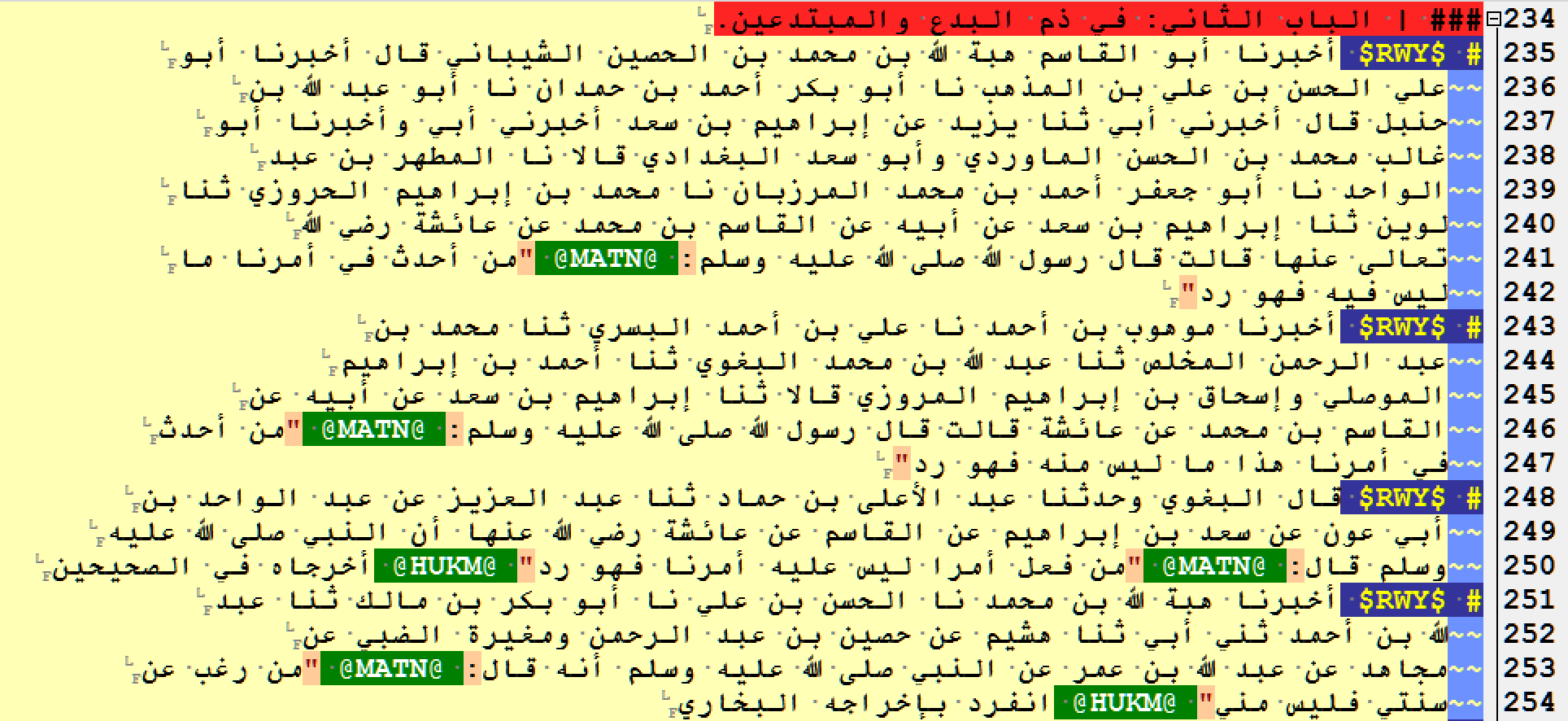

— Riwāyāt units

NB: developed for U Frankfurt Islamic Studies Team; added: August 12, 2016; updated: March 31, 2017

Each riwāyaŧ/ḥadīṯ report should be treated as a separate paragraph: new line + # $RWY$ ; in order to mark the boundary between isnād and matn, @MATN@ tag is to be inserted between isnād and matn. Since it is not uncommon to have an evaluation of reported material, tag @HUKM@ can be used to tag the beginning of the ḥukm-statement. All three elements of a riwāyaŧ/ḥadīṯ must remain the part of the same paragraph.

# $RWY$ this section contains isnād @MATN@ this section

contains matn @HUKM@ this section contains ḥukm .

It is not uncommon that either isnād or matn is missing. In such cases @MATN@ tag still must be inserted: in the case of missing isnād, @MATN@ directly follows # $RWY$ ; in the case of missing matn, @MATN@ becomes the last element in the ḥadīṯ paragraph. @HUKM@ is optional and inserted only when there is a ḥukm-statement.

The following regular expression can help to visually identify sections with isnāds (copy-paste it into the search window of EditPad Pro). The screenshot below demonstrates how a passage of text with lots of transmission terms becomes visible in the sea of text.

\bو?(عن|حدث(نا|ني|ت)|[اأ]نبأ(نا|ني|ت)|[اأ]خبر(نا|ني|ت)|[اأ]?نا|ث?نا|ثني)(( |\n~~)(\w+( |\n~~|\b)){1,3})

Additional Tags (testing)

......- for lacunae in editions (when they are marked as such in editions: naqaṣa fī-l-aṣl, saqaṭa min al-aṣl, etc.). These will be highlighted in red.

Known issues with EditPad Pro

Highlighting scheme running amok

Occasionally it happens that highlighting scheme loses its track and gets shifted, highlighting wrong elements. One of the things that may trigger this behavior is a long regular expression in a search field, but sometimes it happens for some other reasons. This can be fixed through refreshing the highlighting scheme by going through the following steps: [Options >] Configure File Types... > Color Syntax > Refresh (Ok).

Folding scheme does not seem to work

Folding lines is a very convenient tool, but it seems to take a while before for it to load when one opens EditPad Pro. This can be fixed by going through the following steps: [Options >] Configure File Types... > Navigation > Refresh (Ok).

Work in progress

Issues with pagination

Pagination in multivolume texts is sometimes problematic in the following manner: in some volumes page numbers are given at the beginning of a page, while in others—at the end; this is not a major issue, but needs to be fixed eventually; a solution may incude an introduction of more specified tags PageBegV00P0000 and PageEndV00P0000. These tags can be then automatically unified (or, perhaps, preserving both page ‘margins’ which would mark the end of one page and the beginning of the next: e.g., PageEndV05P0456 PageBegV05P0457).

Simplification of mARkdown

In general mARkdown can be simplified at least in the following manner:

~~and#can be dropped and\n\nto be added between logical units (headers, paragraphs), as in the originalmarkdown; this will make it easier to edit texts and there will be less mistakes.- …

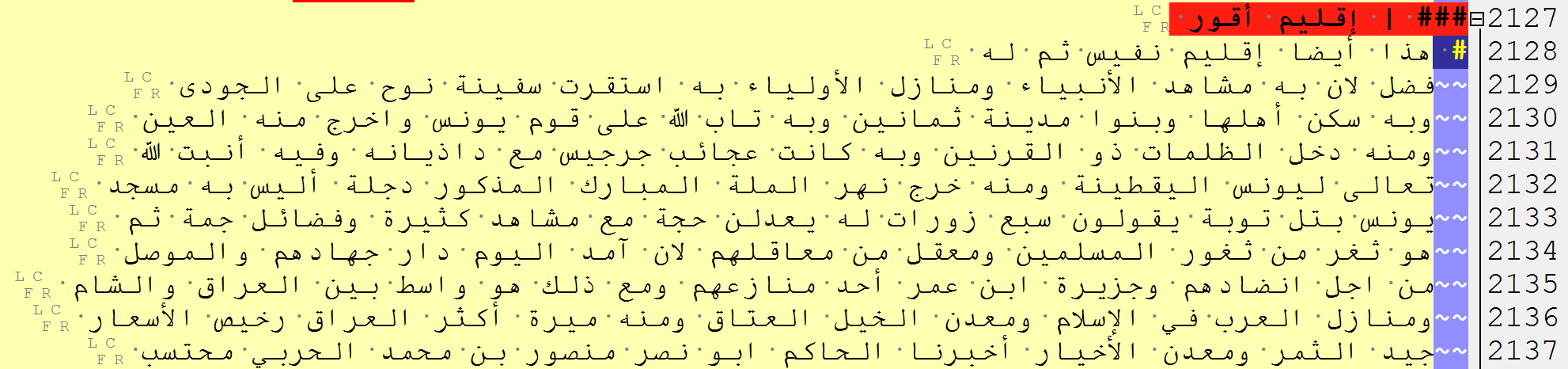

Leave a comment